“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

That well-known quote comes from Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th president of the United States and former Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe. It’s a pithy quote—though perhaps a little overstated—that highlights the critical importance of planning for any serious undertaking.

For a biopharmaceutical company, the decision about how to enter Europe is a big one, and certainly qualifies as a serious undertaking. The opportunities can be great. In many therapeutic areas, the eligible patient pools are comparable to those in the US. There are reliable patent exclusivity periods. Reimbursement processes recognize and reward innovation and outcomes. Collectively, Europe offers a huge market. Plus, the chance for a growing company to break new ground and develop into an international organization is exciting in itself.

Yet, the scale and diversity of Europe brings considerable challenges, as we’ve outlined throughout our series on success in Europe. Success requires data-based decisions to invest the optimum amounts in various capabilities and resources. Equally important is the timing and “gating” of those investments. Responsibility falls on leadership to make decisions that properly balance risk with reward and ultimately maximize shareholder value.

Even a unique product—underpinned with cutting-edge science—won’t sell itself. Unless the product brings an unprecedented value proposition, a value assessment across European markets is needed to help convey the value at the right place at the right time to different stakeholders.

Success requires proper strategic planning. That planning is best organized around addressing three overarching questions supported by the appropriate assessments:

- What is the European opportunity and how can we unlock or maximize it?

- What is our European and market-by-market entry strategy?

- What does the optimal business model look like?

Regarding each question, it’s essential to have clarity and organizational alignment on a “base case” scenario, derive potential scenarios, and determine the degree of risk and sensitivity involved. After all, “Planning is everything.” In this article, we provide some guidance to help leaders conduct the right kind of planning to answer the important questions above.

What is the European opportunity and how can we unlock or maximize it?

To determine the viability of European market entry and inform a go / no-go decision, a market opportunity assessment is foundational. Such an assessment should focus on—and be informed by—a risk-adjusted net present valuation (rNPV) for different potential entry scenarios and sensitivities that considers the expected cash flows and (opportunity) costs. On a corporate level, those scenarios may include potential “go-it-alone” approaches, partnerships, out-licensing arrangements, and so on.

At first glance, developing such a sweeping assessment appears daunting, and a number of valid questions arise:

- How can we do this efficiently for so many markets?

- How good are the data?

- How do we handle all the potential nuances across the region?

A detailed market-by-market analysis would be great. The reality is, building it would drain resources and offers diminishing returns when extended to every single market. So, it pays to be pragmatic and focus on what is necessary to make the go / no-go decision.

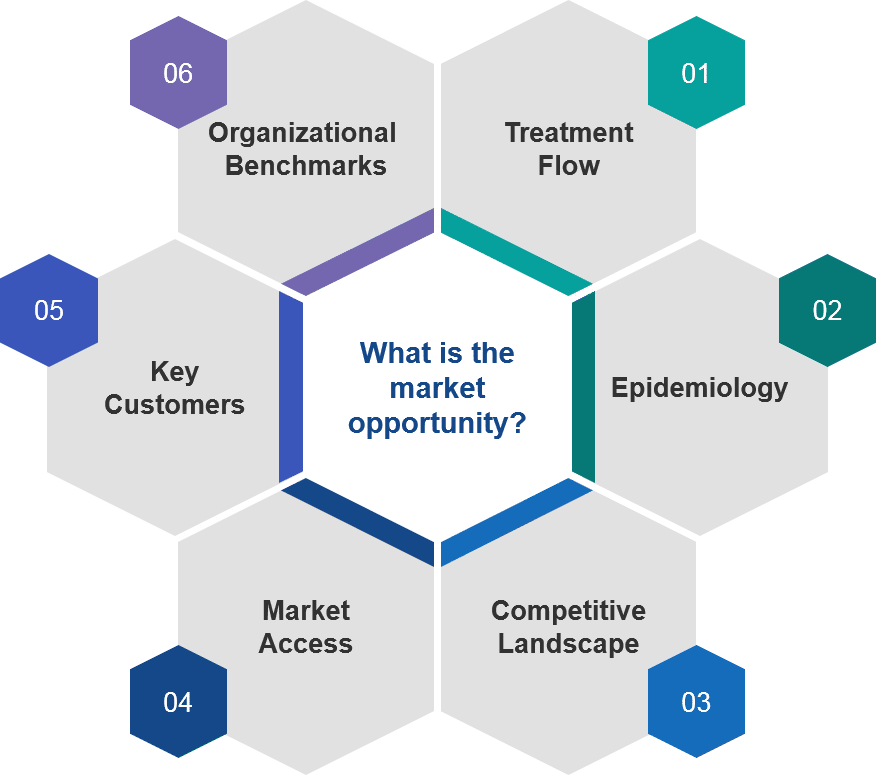

The most common approach is to focus on the top five European markets (the EU5: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), given their significant populations and representative market archetypes. Each market review would typically focus in on six core topics: treatment flow, epidemiology, competitive landscape, market access, key customers, and organizational benchmarks.

Figure 1: Core Components of a Market Assessment

From these insights in key markets, leaders can develop a revenue forecast for the region, making rational extrapolations where necessary. In addition, they can estimate the organizational footprint and associated fixed and variable costs that would be needed to achieve that revenue. The resulting rNPV for each entry scenario—and the according sensitivities— in combination with the overarching corporate vision, strategy and culture will provide a foundation for informed decision making. To illustrate, the NPV number alone will not determine the path, if (for example) there is no:

- Alignment on the achievable target product profile – The key questions here are: What can the science really deliver? What is the real added benefit to patients? What is our confidence in delivering against it?

- Clarity on the required cashflows to fund potentially more promising clinical development – Key questions include: What financial runway do we have? What’s our risk appetite?

- Clear agreement on how to serve stakeholder expectations. Key questions may include: What financial return is expected and when?

These are a few of the questions senior leaders need to align on with their board members and stakeholders to further inform how to enter Europe.

What is our market by market entry strategy?

Once a “go it alone” decision for Europe is made, the need for tighter planning becomes more acute. Given the substantial variation across markets—not just in opportunity size but also in healthcare system and market state—it would be remiss to assume that a single entry strategy can apply across the region.

Now is the time to define a market-by-market entry strategy that recognizes in which countries it makes sense to “go it alone” vs. collaborate with others. The right strategy should deliver on local requirements for success, balance company risk with maintaining the desired level of strategic and/or tactical control, and ultimately optimize the bottom line.

There are several strategic options that could be followed, and we have outlined the major ones here. Partnerships in particular are increasingly innovative and there are several potential approaches to explore in this option alone. Table 1 provides an overview.

Table 1: High-Level Entry Options and Their Pros and Cons

| Option | Details | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Go it alone” Maximum control and return, maximum risk | Fully invest in core capabilities and infrastructure in the market Usually considered for priority markets | Full strategic and implementation control of the launch Likely to generate highest shareholder return in the long-term | May take longer to establish and carries the highest investment |

| Partnership Lower strategic or implementation control in return for new expertise and shared risk | Capability Partnerships – Build a network of partners who can bring local expertise in one or more key areas (e.g., distribution and demand generating services) Joint Venture (JV) – Create a new company with a partner, normally with a mutually beneficial opportunity to share expertise and capability; Customer-facing activities may be led by one company or follow a co-promotion model | Quick to establish expertise and capability Lower cost base | Less implementation control Potentially differing cultures Must relinquish intellectual property (IP) |

| Limited Involvement Risk-minimized at the expense of revenue potential | Out-License – Give exclusive rights to a partner for a fixed or performance-related fee | Easy and quick | Usually no strategic or tactical control; Dependent on partner |

Ultimately, a biopharma company must carefully evaluate their options to make the best decision. The approach should be tailored to the company’s priorities, factoring in the size of the opportunity in each market, and the key pros and cons and barriers to entry, such as challenges related to pricing and reimbursement.

It’s also important to consider each option’s longer-term strategic fit. This is particularly relevant when the company has a pipeline with multiple product assets, and when additional launches may be just around the corner.

What does our optimal business model look like?

Assuming the decision has been made to “go it alone,” it becomes critical to figure out exactly how the company plans to create and deliver real, sustained value to its customers in a financially viable way. In simplest terms, the business model is a clear articulation of how the company plans to make money. Without a solid business model, there is the potential for near- and long-term underperformance, which would have a negative impact on shareholder value. The company’s business model must provide the necessary clarity and properly align all stakeholders.

In biopharma it’s generally a bad idea to attempt to transfer the US business model to Europe as the environments are sufficiently differentiated. Instead, time invested in developing a tailored EU-specific business model is time extremely well spent. There are multiple frameworks out there for developing business models; in fact, it can be confusing to sort through all of the guidance that is available and bring everything together in an effective way. That said, there are some core topics that are a must for any business model to define. These include the following:

- The Customer – To which customer segments are we seeking to deliver value (e.g., patients, physicians, payers, etc.)?

- The Value Proposition – What problem(s) will we solve for each customer segment that will improve their respective situations, and what does our offering look like?

- Preferred Channels – How will we reach the different customer segments to deliver our value, and which ones are likely to be most effective?

- Required Activities – What do we need to do when communicating via our channels to deliver the value proposition with greatest impact?

- Partnerships – Which technologies and/or activities can benefit from support / expertise of others to drive our value? Who are our partners and what are they expected to contribute?

- Revenue – How much do customers pay today and what would they be willing to pay for the proposed value?

- Costs – What fixed and variable investments will it take to get our value proposition into the market and to deliver value to customers?

Defining the business model can take a while, as some elements may require development or evolution over time. It is an iterative and interdependent process that encompasses your European strategy and your business model. Nevertheless, it’s a critical resource that crystalizes for the company how to deliver on the common purpose: To make the European market entry the greatest success possible.

Hopefully, this short article has provided some useful guidance and driven home one key message: Mainly, that proper planning is needed throughout the process of thinking about Europe, deciding to enter Europe, and actually doing it.

A systematic approach is needed to understand the opportunity in Europe and how to go after it, whether alone, via partnership, or through out-licensng (or some combination on a market by market basis). A clear assessment of the available options will help answer that question for your company. Finally, proper planning extends to development of the business model itself. That, after all, is the core of the whole endeavor.

Blue Matter Expert Contributor:

- George Schmidt