Many people working in and around the health care system and the biopharmaceutical industry use the terms “rare disease” and “orphan disease” on a fairly regular basis. Obviously, they refer to any disease that’s uncommon, often with few treatment options (or no treatment options). But what do these terms really mean? What’s the actual definition of a rare (or orphan) disease?

In reality, there are multiple definitions of the term “rare disease”, so it depends on who you ask. To make things a little more complicated, ‘rarity’ covers multiple orders of magnitude when it comes to individuals affected by rare diseases (RDs), ranging from the relatively more frequent “orphan” to the extremely rare “hyper-orphan” setting.

In this article, we help make sense of all this. We review how different authorities define rare diseases and we take a look at their various orders of magnitude. In addition, we provide an idea of the numbers of patients one might expect to see with a given disease at various points along the continuum. Finally, we explore the relationship between disease rarity and the price of therapy to illustrate the fact that developing treatments for the rarest of the RDs represents a big challenge.

Different But Not So Different: Orphan / Rare Disease Definitions

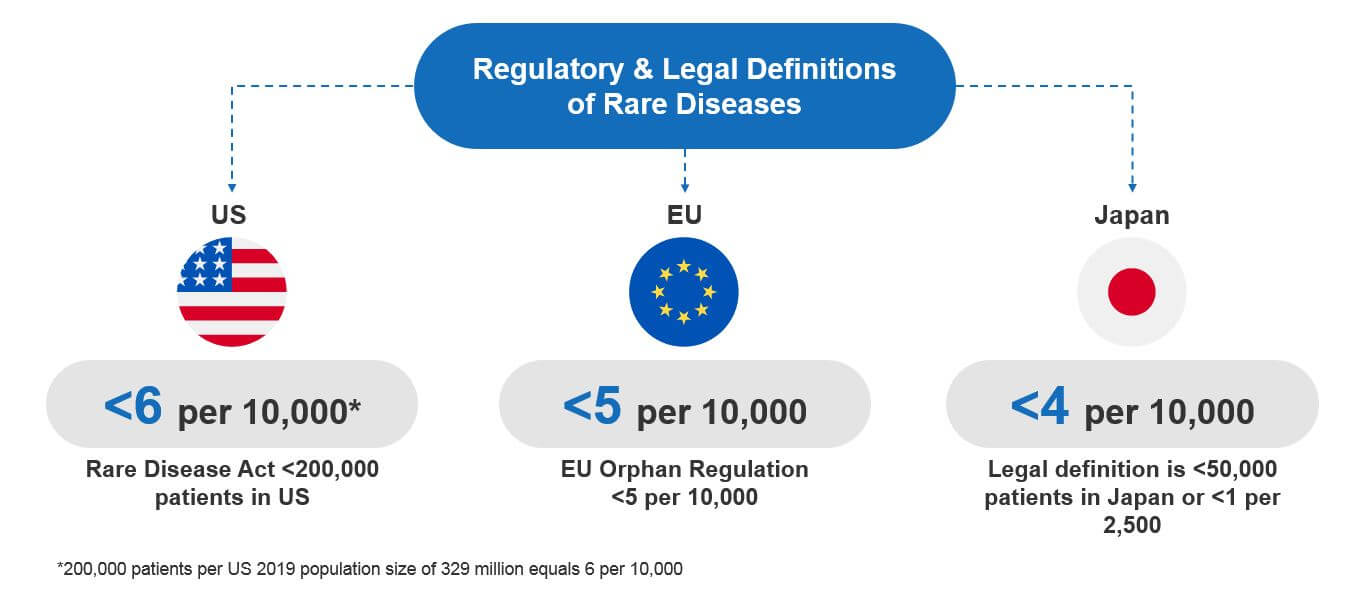

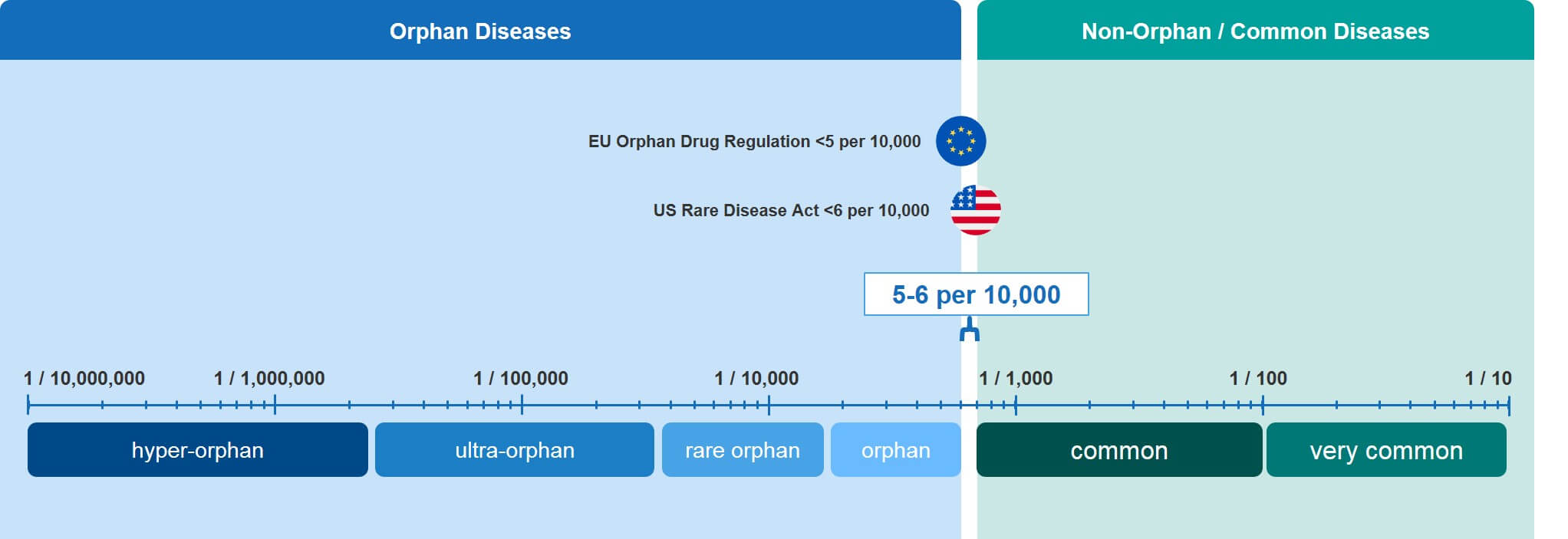

Unfortunately, there is no single, globally accepted definition of what an orphan or rare disease is. So, different national or international authorities have created their own definitions. Most are based on the prevalence of a given disease and on national regulatory and legal frameworks. For example:

- US Rare Disease Act (of 2002): Defines an RD as one affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans.

- EU Orphan Regulation No 141/2000 (Dec 1999): Defines an RD as a condition with a prevalence in the EU of 5 in 10,000 people (or fewer).

- JPN Pharmaceutical Orphan Drug Law (Oct 1993): Defines an RD as a condition that affects less than 50,000 people in Japan or that has a prevalence of less than one in 2,500 people.

At first glance, these regulations seem to define rare diseases differently. However, when you normalize them on a common scale, they are actually quite similar. Each defines a rare disease as one that affects four to six patients (or fewer) per 10,000 people in the general population.

Rare is a Relative Term: The Rarity Spectrum

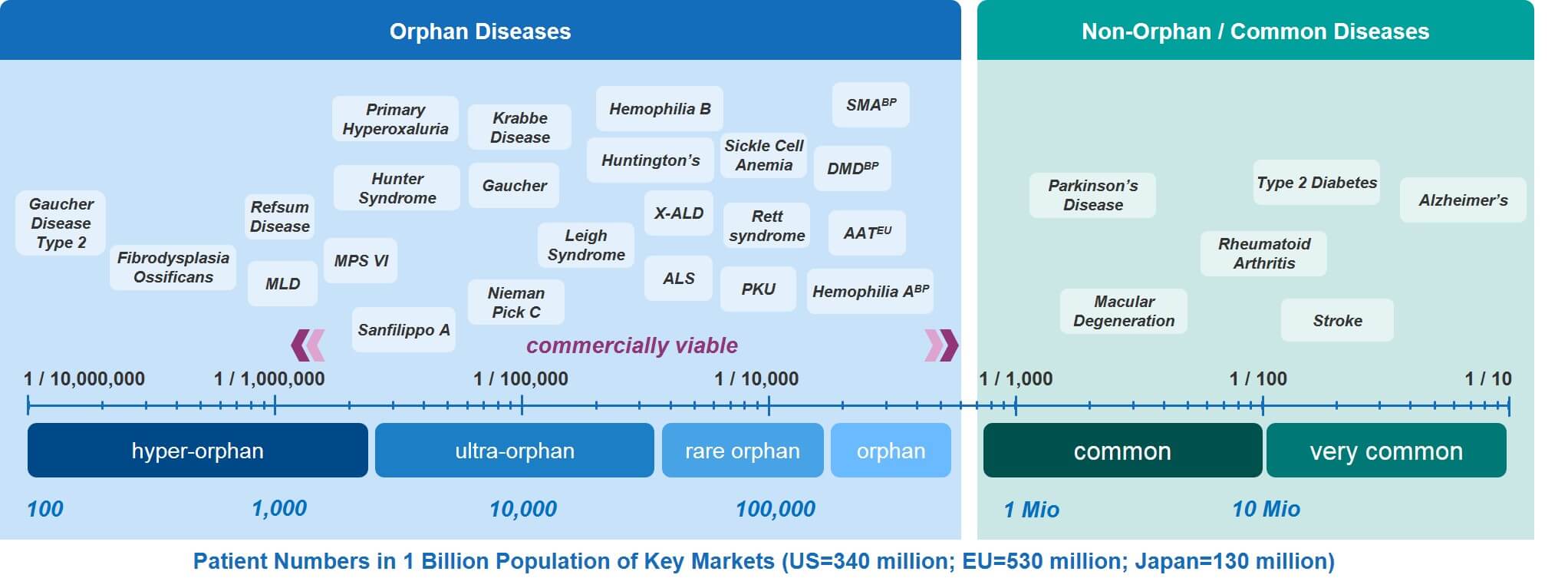

Obviously, not all RDs are equally rare. In fact, RDs can be easily categorized across several orders of magnitude. There is no universally accepted nomenclature for differentiating between the more common RDs and those that are so rare that they only affect a few individuals world-wide.

To facilitate a quicker characterization of RDs according to their position on this very large spectrum, we have attempted to introduce our own nomenclature, as shown in Figure 2. Those diseases that come in just under the limit are simply referred to as “orphan” but progress through other categories as they become increasingly rare: Rare orphan, ultra-orphan, and hyper-orphan.

As we have written before, orphan diseases face special commercial challenges and require a tailored approach to commercial strategy. That much seems pretty evident. However, what’s less evident is that within the orphan disease landscape, commercial approaches must become even more tailored as disease rarity increases. A future article will address that reality in more detail.

Making Sense of The Numbers: From One Patient to a Couple of Hundred Thousand in Key Countries

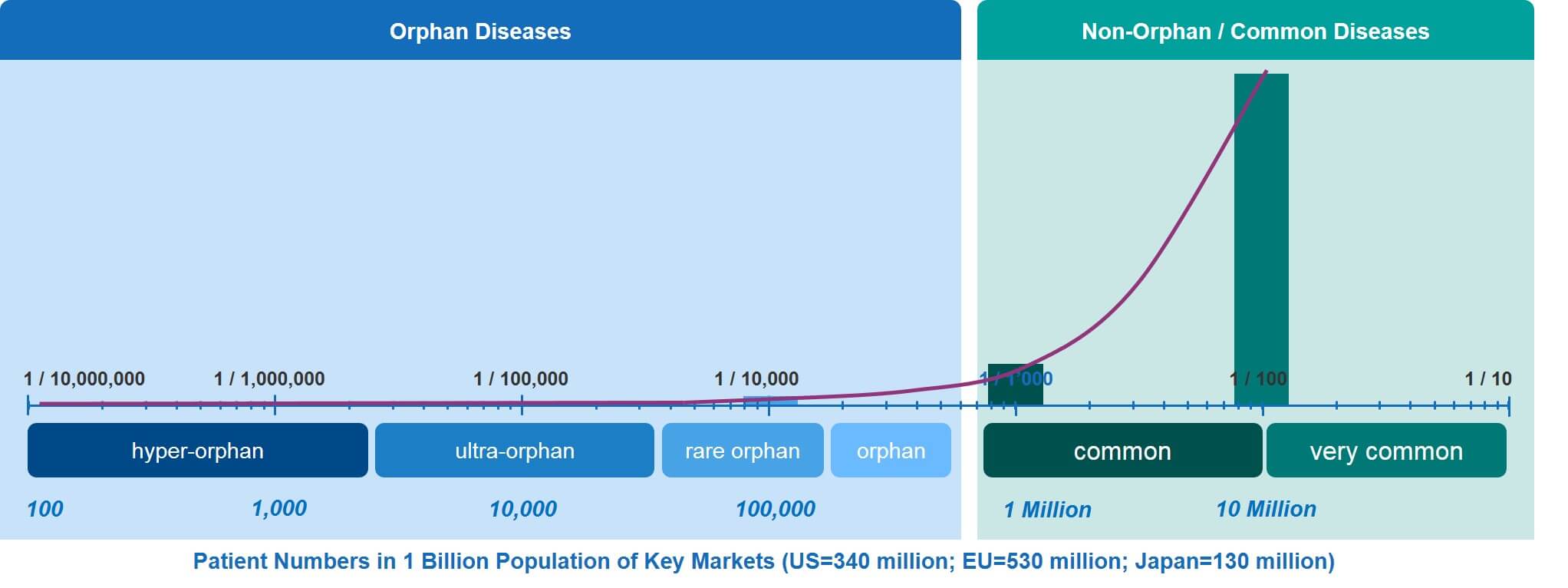

As discussed above, the RD spectrum covers a very large continuum from orphan to hyper-orphan. To illustrate what these somewhat theoretical frequencies mean in terms of actual patient numbers, we have calculated the patient numbers—for any given RD—within the combined populations of the EU, the US, and Japan (which comes to about 1 billion people).

Translating disease frequencies into patient numbers shows that an orphan disease such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)—which occurs at a frequency (prevalence at birth) of about 1.5 individuals in 10,000—will affect about 150,000 male babies. In contrast, an ultra-orphan disease such as primary hyperoxaluria has a prevalence of between one and three per million. That disease will affect 1,000 to 3,000 patients across the EU, US, and Japan.

The even rarer hyper-orphan category affects even fewer patients. In the key markets, there are only about 100 patients affected by Gaucher Disease Type 2, which occurs at a prevalence of about 1 in ten million. Already exceedingly rare, this however is not the end of the spectrum. At the lowest end of it, there are a considerable number of RDs that affect very few individuals, as little as one or two families, or even single individuals. This means that in our ‘key markets’ example, the frequencies can go down to a few cases per billion.

The low patient numbers in the entire orphan / rare disease continuum are nicely illustrated by the curve in Figure 3, especially when compared to the relatively high patient numbers of common and very common diseases.

In Figure 4, a number of rare diseases have been overlaid on the RD spectrum. This provides a range of examples to consider. The source data for these examples comes from the Orphanet Report, Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data, January 2020, available here.

Rarity vs. Cost: Fewer Patients, Higher Prices

While more therapeutic options for rare diseases have been developed over the last decade or so, the fact remains that the vast majority of them—about 95%—remain without an effective treatment option. Some of the more frequent RDs—such as DMD, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), and hemophilia A—represent ‘hot spots’ that have attracted multiple biopharmaceutical players to develop new therapeutic options. This is certainly great news for affected patients.

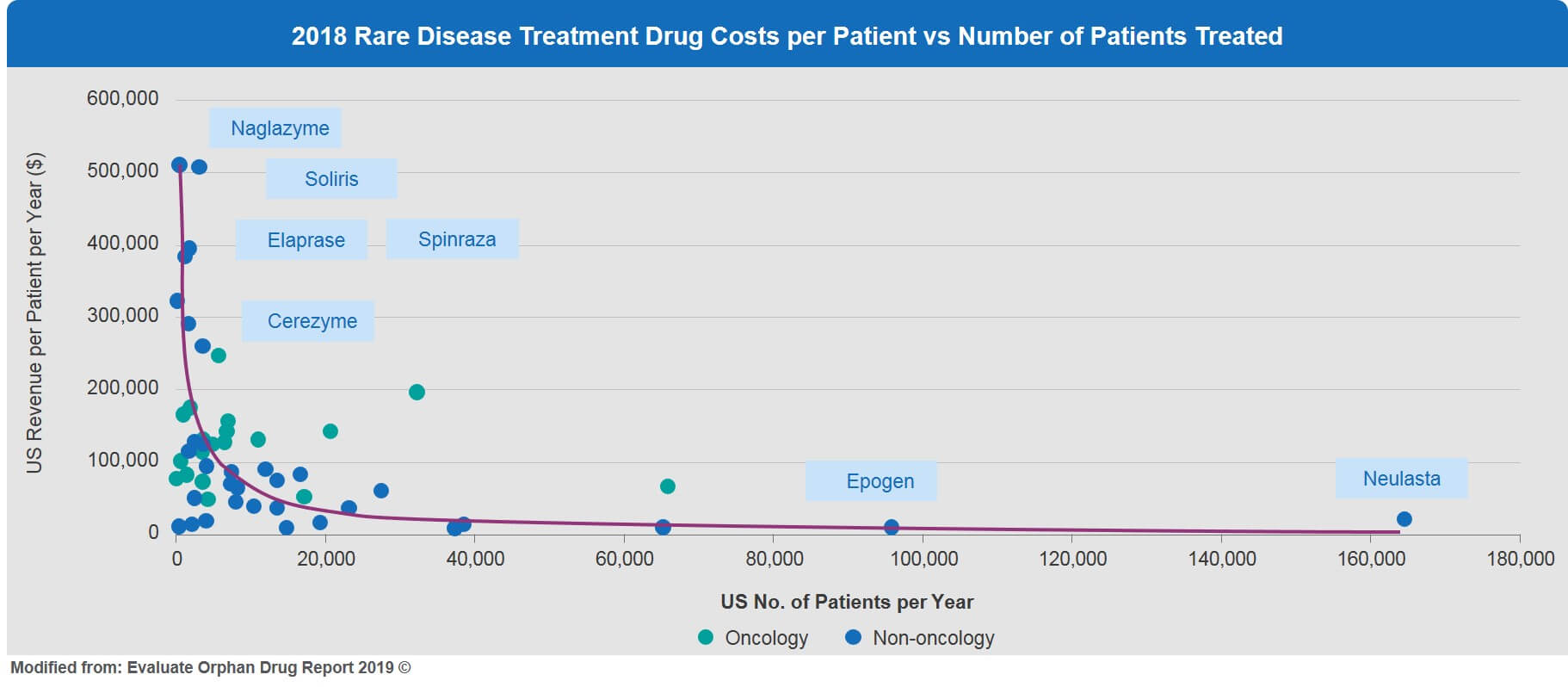

On the other hand, there are much fewer options for less frequent diseases and generally very few or no treatment options for very rare diseases, such as those in the ultra-orphan and hyper-orphan categories. This is largely because rare diseases with very small patient numbers are currently probably not commercially viable. In order to compensate for the very small patient numbers, the complication of conducting much smaller studies, the risks involved, and the prices for such therapies must typically be very high.

This inverse relationship of very small patient numbers and high price is illustrated in Figure 5. For example, enzyme replacement treatments for ultra-orphan conditions such as Naglazyme for MPS IV, Elaprase for Hunter Syndrome, and Cerezyme for Gaucher disease are all priced in the range of $300,000 to $500,000 (US) per patient per year.

For hyper-orphan conditions, drug prices in the current framework might simply become prohibitive, making these rare diseases commercially less viable. This is a real problem for the future development of effective treatment options for rare diseases with very small patient numbers. Novel innovative approaches and solutions are badly needed to encourage the development of affordable, highly tailored therapeutic solutions for these neglected and underserved rare disease patients.

Hopefully, this article has provided some clarity regarding how to define rare diseases, and how they fit along the very large RD spectrum. In a subsequent article, we will dive deeper into the orphan categories and explore how commercial strategy should adjust as rarity increases.