Part Two in a Six-Part Series on Oncology Product Commercialization

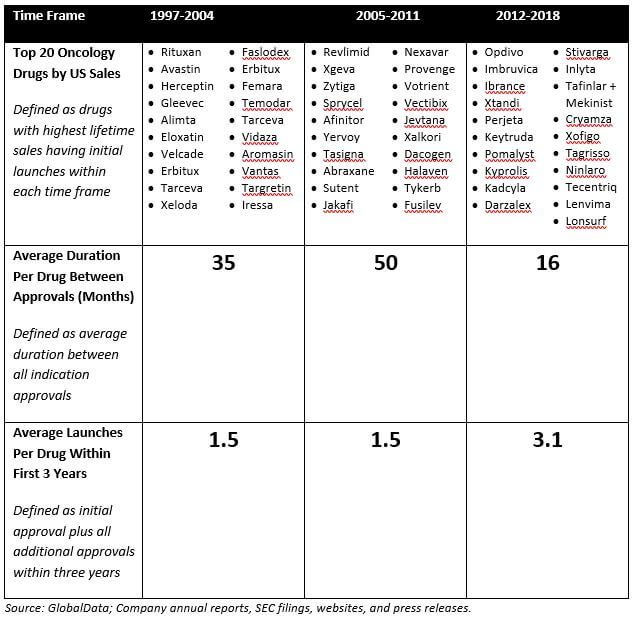

In Part One, we mentioned that the launch frequency for oncology products has increased significantly over the last several years. While this trend is seen in other therapeutic areas across the industry, we believe the combination of factors driving this in oncology are somewhat unique and are related to the current rapid pace of innovation in oncology therapeutics.

In today’s environment, individual products will often launch numerous times—and more frequently—over their life cycles, as they secure approvals in additional sub-populations within a given tumor type, or in new tumor types altogether. This sets up a relatively unique dynamic in which commercial organizations must remain in a constant state of launch readiness, develop efficient systems for staying abreast of the rapidly evolving situation, quickly develop clinical and commercial strategic plans, engage with partners and allies, and execute multiple launches.

Table 1 illustrates this point. It highlights how over the past several years, launches for leading oncology products have been occurring more frequently. For products that first launched in the 2012-2018 time frame, there was a 50% shorter interval between the initial launch and each subsequent approval than for those that first launched in the 1997-2004 time frame. In addition, products that first launched in 2012-2018 have had a greater degree of launch activity than those that launched in earlier time frames, with more than twice as many approvals in their first three years on the market than those that first launched in 1997-2004.

Table 1: Average Time Between Launches; Average # Launches per Drug in First 3 Years

It is fair to say that the above analysis only looks at three distinct time frames and is also largely driven in the most recent time frame by Opdivo, Keytruda, and Imbruvica (although not completely: excluding these three agents by looking just at the drugs ranked 11-20 in each time frame, the findings still hold). However, we believe that this is a meaningful trend that is likely to continue as it is underpinned by two key drivers: An increased understanding of disease biology and heightened competition.

In this article, we’ll explore both of these drivers of increased launch frequency, then focus on three areas that commercial organizations must address to successfully manage this “constant state of launch”:

- Staying abreast of the rapidly changing launch situation

- Conducting launch strategic planning considering the entire product lifecycle

- Understanding how to optimally execute on launch to make the most of the opportunity

Drivers of Increased Launch Frequency for an Individual Drug

Increased Understanding of Disease Biology

An increased understanding of disease biology means that patient populations that were previously treated with a blanket approach (e.g., similar chemotherapy regimens deployed across the full range of patients diagnosed with a specific malignancy) are now being treated differently depending on specific patient characteristics. As a result, drugs are launching more frequently into smaller and/or more clearly defined patient populations.

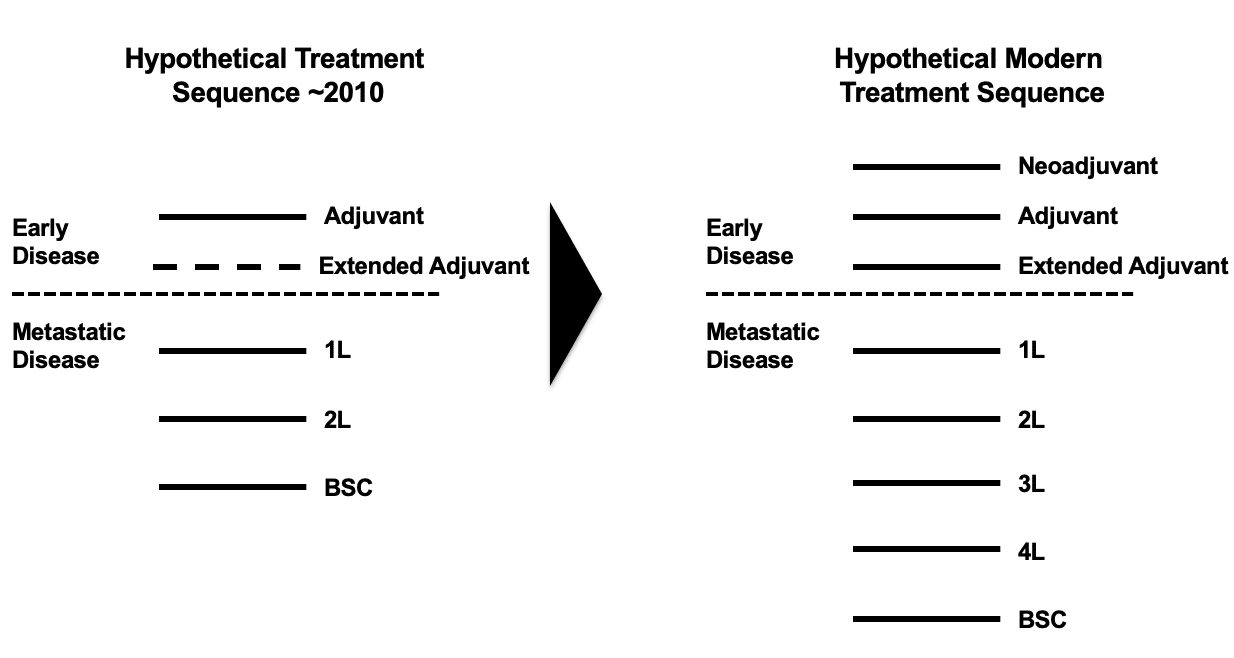

In addition, increased knowledge of disease progression has led to the creation of additional lines of therapy. In early-stage disease, new lines of therapy include neo-adjuvant, adjuvant, and extended adjuvant therapy (extended adjuvant was initially created in 2004 through the approval of Femara in hormone receptor positive early breast cancer, but may be further established as a line of therapy through the approval in 2017 of Nerlynx in HER2+ early breast cancer). In metastatic disease, best supportive care is being preceded with distinct third and fourth lines of therapy. This is being facilitated not only by therapeutics specifically targeting later line patients, but also by extending out single therapeutic approaches over multiple lines and in effect shunting all subsequent therapies down the line. Figure 1 illustrates this trend.

Figure 1: Evolution in Treatment Sequences

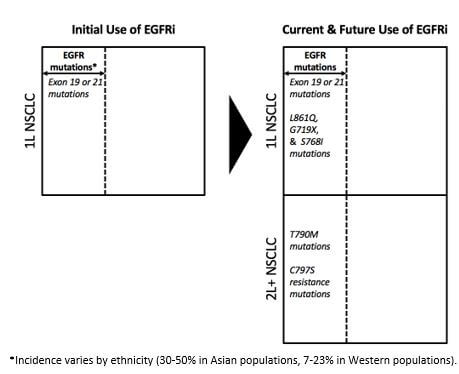

The use of EGFR inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) offers a good example of how therapeutics from a single class have had their use expanded across multiple lines of therapy by targeting different EGFR genotypes—in effect increasing the overall lines of therapy for this malignancy.

Initial approvals for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) were in patients with exon 19 or 21 EGFR mutations (accounting for ~85% of all EGFR mutations). Key products among these initial approvals were the first-generation agents Iressa and Tarceva and the second generation Gilotrif (an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR). Following these approvals, the third generation TKI Tagrisso has been approved in 2L for patients who develop T790M resistance mutations and in 1L for patients with Exon 19/21 mutations, and Gilotrif has an expanded label in 1L for patients with L861Q, G719X, and S768I EGFR mutations.

As a result of targeting a broader number of different mutations, EGFR TKIs are now increasingly being sequenced across 1L and 2L NSCLC, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Use of EGFRi in NSCLC

In addition, the role of EGFR TKIs in patients with early-stage NSCLC is under investigation. All of this is to say that where once targeting EGFR represented a single launch opportunity in 1L NSCLC, it has now expanded to represent multiple launch opportunities across both 1L and 2L NSCLC. In effect, the opportunity has increased along two different axes: laterally across 1L by targeting different mutations within the EGFR mutant space, and longitudinally across 1L and now 2L NSCLC (and potentially into early-stage NSCLC in future).

In general, companies developing oncology therapeutics want to generate clinical data and gain approval in as many of these newly created indications as possible, driving an increase in launch frequency.

Increased Competition

Increased competition, particularly within the big four tumor types (i.e., breast, lung, prostate, and colorectal (CRC)) has led many companies to seek out opportunities in multiple previously underserved diseases with lower incidence (e.g., bladder, renal, and liver). In this way, they seek to capture market share in underserved areas with lower levels of competition.

Competitive pressure is also driving companies to seek clinical differentiation by more aggressively investigating novel therapeutics in combination with other agents. They generally seek to do this either by pairing with the established standard of care or by creating novel combination regimens. An example of the former is in NSCLC, where the PD-1/PD-L1 agents Keytruda and Tecentriq both demonstrated efficacy in combination with the previous standard of care Alimta. An example of the latter is also in NSCLC, where the immunotherapies Opdivo and Yervoy are being tested together in combination.

In addition, the amount of time any first-in-class or second-in-class molecule has in a given indication prior to the arrival of additional competition is getting shorter, driving the need to be constantly expanding out to adjacent indications. One exception to this is if a molecule is able to become the backbone of therapy (through being highly combinable and/or meaningfully clinically differentiated from in-class and out-of-class competitors). However, these opportunities are limited.

Gaining approval in first line is increasingly attractive, as it offers the greatest protection from competition and the greatest potential for becoming a backbone (in 1L as well as through subsequent lines of therapy). However, it is becoming harder to achieve due to higher clinical standards, difficulties of clinical study accrual, and more expensive clinical costs. This paradox, and understanding the trade-offs associated with it, is something that drug developers should seek to understand early in the development of their clinical programs.

Additional factors related to competition that are causing an increase in the frequency of launch include the development of more advantageous routes of administration (such as sub-cutaneous formulations of infused products) and the development of immunotherapies (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1, CAR-T) with broad applicability across tumor types and/or high potential for combinability.

Finally, the more permissive US regulatory environment, as evidenced by the establishment of programs such as Breakthrough Therapy designation and the willingness to grant approvals based on phase 2 and phase 1b clinical data, is also driving increased launch frequency.

Our intent with this article is to provide a series of observations that may help companies understand the oncology landscape, how it is changing, and what that may mean for their launch planning efforts. The goal is to help companies ensure they are properly structured and equipped to succeed in today’s environment.

Constantly Evolving Launch Situation

Inherent in the strategic planning process is developing an understanding of the target market and how it is likely to evolve ahead of a product’s launch. Building and maintaining this understanding requires that an organization invest in creating tools and processes for gathering and assessing updates to the market and competitive situation. This is especially important in oncology, where the market situation is particularly fluid and dynamic.

The most basic part of any monitoring system should keep decision makers abreast of new molecules entering development. That’s the easy part, as any number of commercially available databases and subscription services can help do this. For commercial teams, the harder part involves assessing this data and working to anticipate the strategic implications for their own assets.

A proliferation of new oncology assets in clinical development means that on a practical level, there are an increased number of clinical datasets that have to be tracked and analyzed. Compounding this issue is the emergence of novel datasets (e.g., real-world data, patient-reported outcomes data, HEOR data) that often complement clinical datasets and have to also be incorporated into the team’s perspective.

Furthermore, many of these clinical datasets include novel endpoints whose commercial impact is still to be fully understood (e.g., minimal residual disease [MRD], tumor mutational burden, pathological complete response [pCR], and—to a lesser degree—hazard ratio), introducing yet more uncertainty. Some molecules are also seeking approval in patients across multiple tumor types based on the presence of specific mutations (e.g., Loxo Oncology’s Larotrectinib in patients with TRK gene fusions), further complicating the situation.

In addition, regulatory changes have made development timelines less predictable. In the past, it was fairly straightforward to estimate an asset’s likely approval date. This has become much more challenging in oncology. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is quite willing to accelerate development and review timelines via Breakthrough Therapy designations and other mechanisms and the acceptance of smaller clinical datasets. Companies are also becoming much more inventive in leveraging available tools and regulations to speed their time to market.

Consider the combination of Keytruda (a PD-1 inhibitor) and Alimta (a standard of care chemotherapy) in front-line NSCLC. That combination secured approval on the basis of the phase 2 KEYNOTE-021, Cohort G study, which had only 123 patients. The current phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 study is essentially the same study with many more patients. However, it’s taking place post-approval.

The bottom line is this: Biopharmaceutical companies must build and maintain internal systems and processes for monitoring the environment, identifying new assets, and estimating their potential approval and launch dates. Coupled with this monitoring must be efficient approaches for assessing the likely strategic approach for those competing assets, as well as determining the potential implications for a company’s own oncology portfolio.

Strategic Planning

In a competitive environment that includes an expanding range of tumor types, sub-populations, competitive entrants, and potential combinations, decision makers must be able to confidently determine “where to play.” This requires an approach for thoroughly identifying and evaluating an asset’s areas of highest development priority (tumor types and/or sub-populations), prioritizing them, and then deciding how to allocate clinical and commercial resources accordingly.

Due to the increased frequency of launches, decision-makers need now more than ever to undertake strategic planning that encompasses the entirety of the product lifecycle (i.e., considering all anticipated launches for a product) so that they can understand the trade-offs associated with prioritizing different indications.

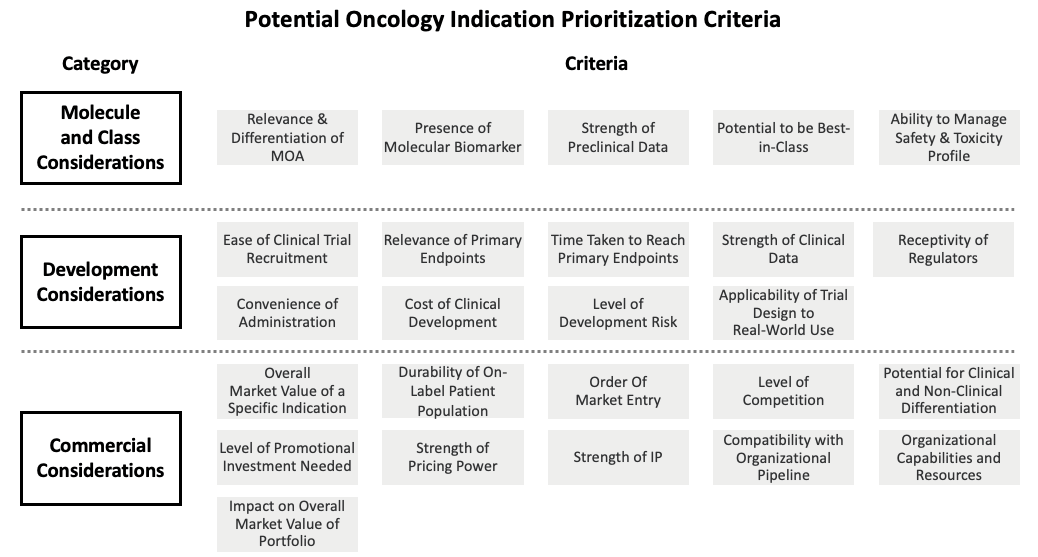

Figure 3 illustrates some of the key criteria that can be used to adjudicate the relative attractiveness of different potential indications. However, it is important to note that companies should apply a different lens to these criteria depending on their own unique situation. For example, criteria should be weighted differently and should have different thresholds for what is considered acceptable, depending on factors such as the company’s growth expectations, what sort of therapeutic focus they want to have, presence of other portfolio assets, appetite for risk, and willingness to enter competitive market places. In addition, companies must consider the impact of indication prioritization decisions on their broader portfolios, as this may impact decision-making. For example, if it is possible to set a high price in a small indication, then it may make sense to prioritize that indication over a second, larger potential indication, as the pricing advantage could be carried through to that larger indication.

Figure 3: Potential Oncology Indication Prioritization Criteria

Identifying and evaluating all potential areas of opportunity at the tumor or indication level may seem like an onerous task. To a certain extent, it can be. However, any strategic team must use its best judgment to decide where to begin its analytical process. For example, a team may limit the scope of its analysis to quickly remove non-viable options if the product warrants it (such as an EGFR inhibitor focused on EGFR-positive patients in a narrow range of tumor types).

The point is: Any successful oncology franchise must put in place ahead of time an appropriately scoped analytical framework to guide strategic leaders as they decide where to focus. These decisions must be made with speed and confidence, and the entire process does not lend itself well to being managed in an ad hoc, unplanned manner. The framework and systems must be in place ahead of time. After all, the time to develop a game plan is before the game starts, and not while it is already underway.

Once the team has determined a prioritized set of indications to focus on and the optimal launch sequence, the focus needs to switch to “how to win” with the initial launch indication. In oncology, as introduced earlier in this article, there is an increasing need to have a targeted approach due to the typically high (and still increasing) levels of competition that will have to be faced.

Furthermore, once the clinical program has delivered data and the market has inevitably undergone further evolution in the interim, there is frequently a need to take a dispassionate, hard look at the opportunity and determine whether there is a need to further narrow the development and commercial focus. It is possible to succeed with a broad approach, but this is significantly easier if the molecule is either first-in-class or best-in-class. Increased competition decreases the likelihood of either eventuality coming to pass, and so the difficult decision may have to be taken to narrow the commercial focus to a sub-set of the potential patient population where there is an opportunity to clinically differentiate the molecule.

Teams will have to frequently reevaluate their launch approach not only with the lead indication but also with the prioritized lifecycle indications to make sure that these remain the correct choices. This reevaluation should take place in the context of external factors (e.g., competitor activity) as well as internal factors such as the confirmation through data of the basic hypotheses about the relevance of the molecule or MOA for the prioritized indications. In addition, the clinical development plan (CDP) should be reviewed to ensure that it is likely to generate data that will make the molecule competitive in these indications. If this is not the case, then either the CDP will need to be adjusted (e.g., by adding or amending studies, end-points, or statistical analyses) and/or the indication prioritization will have to be adjusted.

Launch Excellence

It should go without saying that any organization responsible for managing multiple launches for each of its assets must be as operationally efficient and effective as possible. Given the need to build momentum for a product by maximizing the impact of each launch, mistakes can be costly. In today’s ultra-competitive environment, a given oncology product is likely to have less time than is typical to capture market share and reach peak revenues in a given tumor type or sub-population, and will likely have less meaningful clinical differentiation to work with.

To help ensure the proper level of launch excellence, companies must be willing to invest in multiple launch teams, enabling the company to manage multiple overlapping or near-overlapping launches. These teams must be well-integrated, cross-functional, and equipped with the right tools and processes.

For launch planning and management, the right tools and processes can mean a lot of things. However, answering the following questions can help to hone in on the optimal approach:

- To what extent do we need to factor in operational overlap across different functional teams?

- What are the highest priority launch deliverables for each functional team and are they truly critical to executing on the launch strategy?

- How can we de-risk our approach by identifying activities that can be gated on specific milestones?

- How can we ensure that teams across medical, commercial, and access-related functions are appropriately coordinated?

Establishing best-in-class launch processes—and the tools to enable them—up front is vital. Despite the long product lead-times in this industry, many launch activities and launch capabilities take a long time to develop, and therefore need to be mapped out in plenty of time. Commercial teams do not have the luxury of conducting a launch, doing a post-mortem to see what went well and what should be improved, and then applying learnings to the next launch. Things happen far too quickly for that approach.

Conclusion

The rapid innovation taking place in oncology is exciting for all involved. It’s potentially opening up an entire new world of treatment opportunities and helping us take a giant leap forward in the fight against cancer.

For commercial teams, however, there’s no rest for the weary. To succeed in a dynamic world of active competitors and rapid-fire launches, they must be smarter and more strategic. They must have the right systems in place for quickly prioritizing and re-prioritizing lifecycle opportunities and launch strategies, identifying and prioritizing the most attractive opportunities, developing strategies for seizing them, and executing their plans with confidence.