Nobody ever said that developing and commercializing a new therapy is an easy task. We all know the failure statistics, challenges involved in development, and investment requirements. We’re also aware of myriad time-sensitive details that seem to multiply during the pre-launch and launch time frames…and we know how challenging it can be to successfully commercialize a therapy in a competitive environment. For some therapeutic areas, however, the challenges and difficulties are a bit more intense, driven by factors that are either unique to the therapeutic area or magnified within it. CNS is one of those areas.

Of course, CNS is an umbrella term that includes a broad range of diseases that can be radically different from one another, ranging from highly prevalent psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD) to rare neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease. However, there are several interesting challenges that are commonly seen across multiple disease states and market segments within the broader CNS universe. These challenges may not always be present for every therapy, but they are common enough to be characteristic of the CNS market, and they require special attention from decision makers within biopharma companies.

In this paper, we describe a few of the highest priority challenges, along with the implications for manufacturers seeking to develop and commercialize CNS therapies. In future articles, we will dive deeper into the individual challenges, describing how manufacturers can plan for, mitigate, and address them in their development and commercialization plans.

Challenge 1: Heterogeneity of CNS as a Disease Category

As mentioned above, CNS is an extremely broad umbrella term covering a wide variety of diseases. Consider that CNS can include diseases that have different:

- Symptomatology – Such as psychiatric, cognitive, sleep and motor symptoms, as well as pain and others

- Etiologies – Including monogenic (e.g., Huntington’s disease), partially genetic, environmental, unknown, etc.

- Prevalence – Ranging from rare diseases like Rett syndrome to more prevalent diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and autism

- Patient populations and demographic groups – Ranging from pediatric diseases like spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) to those that predominantly affect elderly people like Parkinson’s disease

- Treating specialists – Which can include neurologists, psychiatrists, sleep specialists, and a host of others

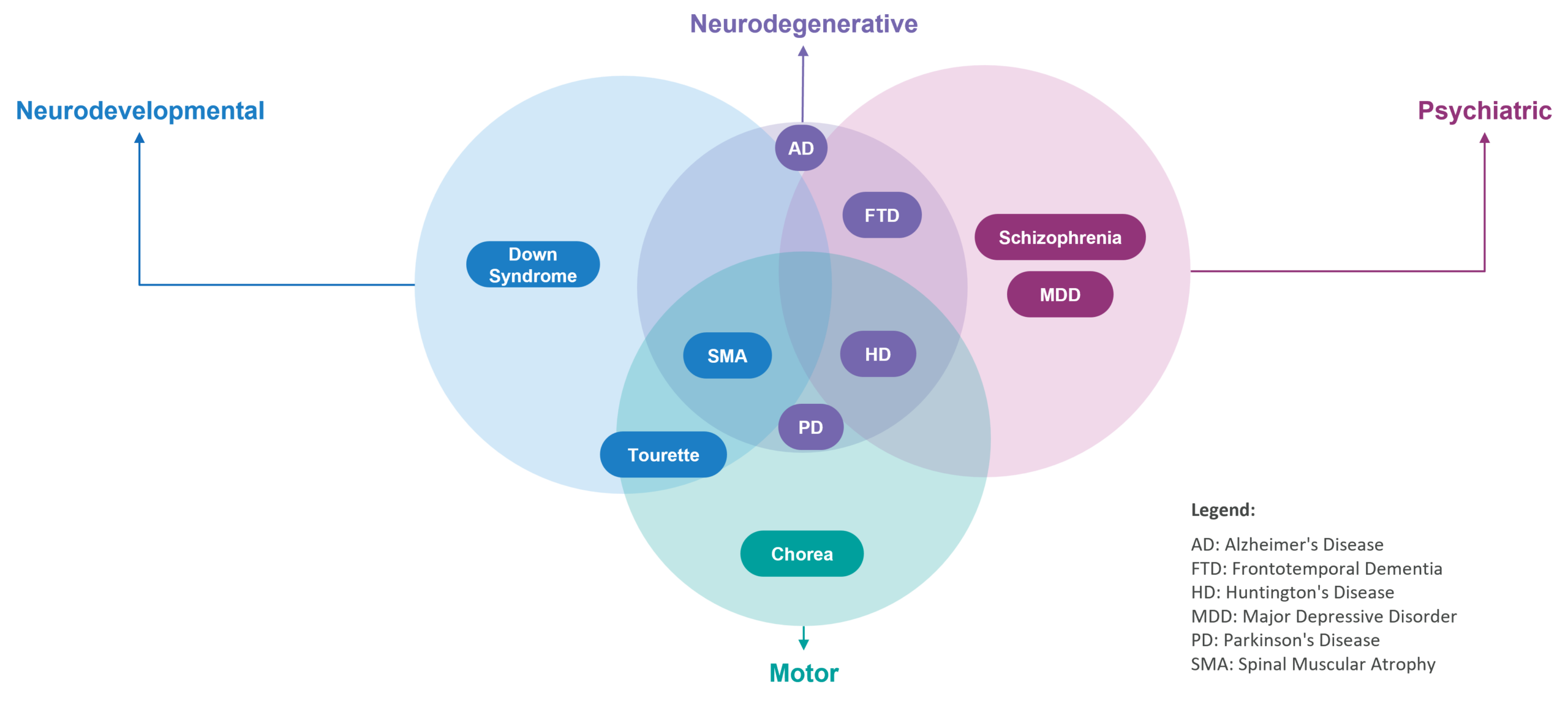

While categorization is helpful to organize how we think about the CNS landscape, many of these categories are overlapping, which contributes to the challenge of characterizing the CNS landscape. For example, Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that has elements of psychiatric diseases (such as schizophrenia and depression) and motor coordination disorders (such as Tourette syndrome). Said another way, there is no categorization for CNS similar to the neat way in which we can categorize disease areas within oncology (such as by organ where the tumor originates).

Figure 1: Examples of Overlapping Disease Categories in the CNS Landscape

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

This somewhat chaotic reality presents unique challenges for companies that want to be CNS portfolio companies. From a development perspective, if decision makers want to focus on a category within CNS because they assume there is some common characteristic across those diseases that enable the company to develop one drug across multiple diseases, then it may be very difficult to do so. The heterogeneity of diseases even within a single category will make it substantially more difficult to deploy a “pipeline in a program” development strategy.

From a commercial perspective, there may be minimal synergies across CNS indications. For example, a company focused on the cardiovascular space can build relationships with KOLs and other key stakeholders and develop a customer facing organization for one cardiology indication. Then, all of that can largely be leveraged for another cardiology indication due to the overlap in settings of care, treatment decision makers, and so on. However, a CNS company developing simultaneously in postpartum depression and schizophrenia—two indications within psychiatry—may have to take fundamentally different approaches.

Challenge 2: Patient identification

Above, we focused on the fact that there is significant heterogeneity across the broad CNS space. It doesn’t stop there, though. That same reality is also evident within individual diseases. CNS diseases are often heterogeneous in presentation and can fall on a spectrum. The classic example is autism spectrum disorder. Another example is Alzheimer’s disease, which is thought to include a variety of different types of dementias.

Furthermore, many CNS diseases lack definitive tools for early, differential diagnosis (such as diagnostic biomarkers) and have complex / qualitative diagnostic processes that can often be based on symptomatology rather than a specific, accurate, confirmatory diagnostic test. For example, even the diagnostic process for ALS, a relatively well-characterized CNS disease, is multifactorial and includes clinical, neuropathological, electrophysiological, and in some cases genetic tests, with no single test able to provide a definitive diagnosis.

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

In short, patient identification is typically more challenging. It’s relatively common to see delays in diagnosis, as well misdiagnosis before finally zeroing in on the disease. In some cases, diagnosis may occur when it is too late to meaningfully treat the disease. This is particularly important for neurodegenerative diseases where the damage progresses over time due to neuronal loss.

Overall, this presents unique challenges for clinical trial recruitment and enrollment. A key goal is to recruit a patient population with consistent, measurable disease characteristics (severity etc.) so that the trial endpoints can be robustly measured. Challenges in identifying the right patients may lead to heterogeneity in the trial population, which adversely impacts the ability to measure an experimental therapy’s efficacy.

Challenge 3 – Limited Objective Measures of Disease Severity and Progression

In many CNS diseases, there are few definitive, clinically meaningful endpoints and biomarkers to objectively measure treatment efficacy and/or disease progression. For example, many endpoints are based on patient- or caregiver-reported descriptions of symptoms. The clinical global impression (CGI) scale for Angelman syndrome is an illustrative example. It is used to measure the severity and improvement of symptoms. Obviously, it’s very different from a purely objective measure such as a blood test or scan to measure the size of a tumor.

Also, remember the multi-dimensional nature of many CNS diseases. Huntington’s disease, which was mentioned previously, has symptoms across many domains, including motor, psychiatric, and cognitive. Because of this, some endpoints are composite scores across multiple dimensions of symptoms, which can make it more challenging to isolate and demonstrate an effect.

CNS diseases are often progressive and, given the tendency toward later diagnosis, it can be very challenging to reverse the disease process. As a result, efficacy often means stabilizing a disease or slowing the rate of progression (rather than improving it), which can be more difficult to measure in the context of a clinical study.

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

Qualitative and/or imprecise endpoints contribute to challenges in detecting the effects of a treatment in a clinical trial. This can lead to

- Fewer patients in CNS clinical studies and more trial failures; This has been borne out by the data, as a recent publication noted that one of the biggest drivers of reduced R&D productivity was a portfolio focused on CNS therapies

- Increased level of financial risk for CNS manufacturers, which may increase the need and difficulty of raising capital in public or private financial markets

- Challenges in articulating the value proposition of a novel treatment to physicians, payers, and other stakeholder groups

Challenge 4: Treatment Delivery

The brain has a unique status as immune privileged or protected due to the blood brain barrier (BBB). This allows only certain essential substances, such as oxygen, glucose, and amino acids to pass through, thereby protecting the brain from potentially harmful substances present in the bloodstream including pathogens, toxins, and large molecules. This selective permeability helps maintain an optimal environment for brain function.

The BBB can also prevent penetration of many therapeutics into the central nervous system, particularly larger macromolecules such as monoclonal antibodies. However, even small molecules can have variable CNS penetration.

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

From a development perspective, there are significant implications, such as

- The need—during the R&D process—to optimize a therapeutic’s ability to penetrate the CNS

- The increased risk of failure: Even if the company gets the mechanism of action (MOA) right, the drug may not be making it to the brain in sufficient concentrations to act on its target

- Challenges with therapeutic index: A drug may need to be delivered at higher concentrations to get a sufficient concentration in the CNS, which may increase the risk of systemic toxicity

From a commercialization perspective, delivery of therapies to the CNS may necessitate more invasive or specialized routes of administration (ROAs), such as intrathecal injection. Not all treating healthcare providers (HCPs) may have experience with these types of techniques, which may necessitate specialized equipment or training.

These requirements may also impact broad uptake of certain CNS therapies and increase the burden on neurology practices and workflows. Consider Spinraza® for SMA, which requires intrathecal injection. While intrathecal administration has been critical for the treatment of pain for decades, Spinraza was the first intrathecally injected disease modifying therapy for a neurological disorder. However, its US market share is expected to be surpassed by Evrysdi®, which is an oral option for the same indication, pointing to the challenges of broad uptake of intrathecally administered drugs.

Challenge 5 – Complex Patient Journey with Fragmented Treatment Decision-Makers and Approaches

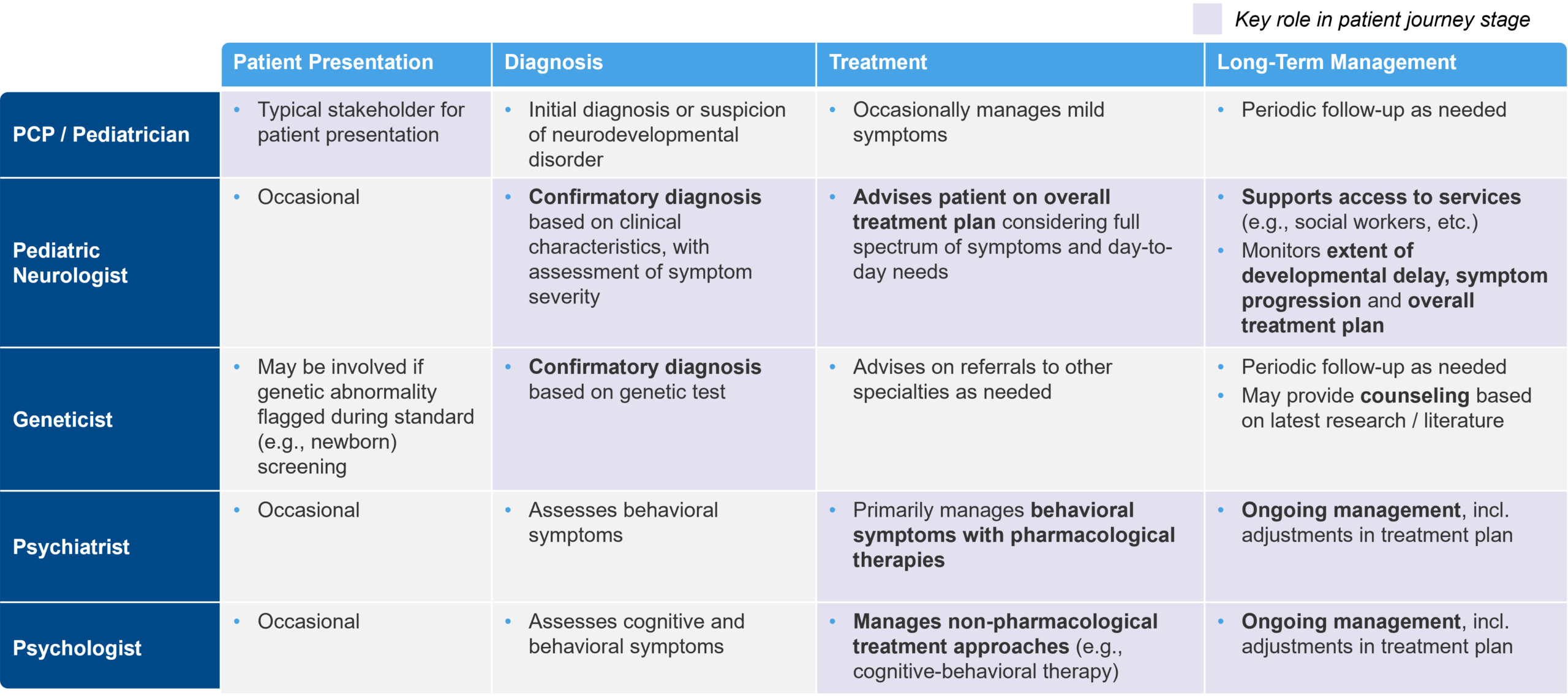

As mentioned earlier, the patient journey with CNS disorders can be complex, involving a diverse multidisciplinary group of HCPs that contribute to diagnosis and treatment. To establish a confirmatory diagnosis, patients may need to be referred from physician to physician. These referrals take time and can be inefficient. They also bring the risk of losing critical clinical data, test results, and other information between physicians.

In addition, treatment approaches for CNS disorders are often combinatorial, and may include cognitive behavioral therapy, motor / occupational therapy, pharmacological treatments, and other approaches to address the multifaceted nature of a given disorder. Each treatment approach may be “owned” by a separate HCP, leading to a “fragmented” treatment decision-making approach.

Figure 2: Example HCP Stakeholder Roles for a Patient with Fragile X Syndrome

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

In this type of environment, it can be difficult to drive the adoption of new therapies. Patients are often on multiple therapies, including pharmacological and behavioral, physical, and/or occupational. It needs to be clear how a novel therapy fits into the existing treatment paradigm. Does it replace another option? Does it synergize with a specific approach? Does it address a specific set of symptoms typically managed by one HCP, or is it a disease-modifying therapy that needs to be administered by a “quarterback” HCP that has a broader purview into the patient’s treatment plan?

Overall, this factor can make it difficult to identify and engage the appropriate treatment decision maker. This is especially true when commercializing a pharmacological therapy for a disorder that has limited precedent for pharmacological treatment.

Challenge 6: Landscape Dominated by Low-Cost Generic Symptomatic Therapies

For most CNS disorders where effective disease modifying therapies are not yet available, the only pharmacological therapies are focused on treating symptoms. Many of those therapies are generics that may or may not be indicated for the specific disorder in which they are used.

For example, in Parkinson’s disease, the major classes of pharmacological therapies used to treat the motor symptoms associated with it are generic. These include MAO-B inhibitors such as rasagiline, dopamine precursors such as levodopa, and dopamine agonists such as pramipexole. In Alzheimer’s disease, generic anticholinergics such as donepezil were the standard of care prior to the approval of Leqembi®. They may continue to be, as Leqembi’s uptake has been slow so far.

HCPs, patients, and payers have grown accustomed to the easy access and low cost of these symptomatic therapies, even though they may not be particularly effective or address the underlying disease process. This ease of access may enable patients to cycle through symptomatic therapies (e.g., atypical antipsychotics for psychiatric disorders) until they find a treatment option that works best.

Implications for Biopharma Decision Makers

Given the cost differential of a new branded therapy vs. a generic, manufacturers will have a higher burden of proof to demonstrate a clinical risk-benefit profile that justifies the price point. This may be especially challenging ex-US, where many markets include cost effectiveness in their evaluation of novel therapies.

Introducing a high-cost branded therapy into a disease space that previously had only generics may cause challenges with payer coverage, especially in more prevalent disease areas that have a greater budget impact for payers. This dynamic was recently demonstrated when Medicare was unwilling to reimburse Leqembi outside of the CED (Coverage with Evidence Development) program until Eisai received full FDA approval for the drug. Based on payer willingness to cover a novel branded CNS drug, challenges may arise with patient affordability, particularly for disorders that have high proportions of uninsured or underinsured patients.

Coming Next

The intent of this paper is to provide a deeper understanding of the key challenges that are characteristic of the CNS space. By design, it has been long on challenges and implications, and very short on solutions. However, in upcoming papers, we’ll explore each of these challenges in more detail, deepening our understanding of them, as well as describing some potential solutions that biopharma decision makers can use to overcome them, or at least mitigate their effects. To stay up to date on our latest publications, please follow Blue Matter on LinkedIn or check our blog on a regular basis.