Part 2 in a Series on Rare Diseases

Part 1 of this series provided an overview of rare diseases and the special challenges they present to biopharmaceutical companies. In this installment, we explore one of the most basic—and most confounding—of those challenges: Finding patients.

In the European Union, a disease is considered rare when it affects fewer than five in 10,000 people. In the United States, a disease is defined as rare when it affects fewer than seven in 10,000 people.1 Some diseases are far rarer. Huntington’s disease, for example, only affects 3 to 7 per 100,000 people of European ancestry (and is even less common in other populations).2 And, compared to some other ultra-rare diseases, Huntington’s disease could seem somewhat common.

As one would expect, rare diseases mean rare—and typically geographically dispersed—patients. That makes them hard to identify, and this presents significant problems for three key stakeholder groups: The patients themselves, the physicians who treat them, and the pharmaceutical companies that are working to develop new treatments.

Impacts of Patient Rarity on Key Stakeholders

Patients

The “typical” rare disease patient faces a range of obstacles before ever getting a proper diagnosis. Often, primary care physicians have limited (or no) familiarity with the patient’s condition, and refer the patient to a specialist after being unable to determine the cause of the patient’s symptoms.

Unfortunately, the patient’s journey usually does not end with the specialist. Depending on the disease, awareness among specialists can be similarly limited, and patients will often see multiple doctors on their journey to a diagnosis. It can take numerous doctors and multiple misdiagnoses and hence, a long period of time before the correct rare disease is identified.3

In a survey from EURORDIS documenting the delay in rare disease diagnosis, 40% of patients received an initial diagnosis and treatment that was wrong; about a fourth of patients had to wait between 5 and 30 years until the correct diagnosis had been established.4

Obviously, this process can be frustrating for the patient and his or her family. Frustration, however, is the least of the burden. Delays in diagnosis and proper treatment reduce the patient’s quality of life, and can increase morbidity and mortality. It’s common sense, but it’s true: The more quickly a patient can be diagnosed and treated, the better off they will be.

Physicians

Patient rarity also impacts physicians. As stated earlier, general practitioners (GPs)—and even specialists—often have very low awareness of a given rare disease. This is particularly true when there are no treatments for the disease and little interest in it.

GPs are very unlikely to diagnose and treat a rare disease, and will usually refer patients out to a specialist. In most cases, specialists also have limited knowledge of rare diseases. For a particularly rare disease, a specialist may only see one patient in his or her career. The specialist is often uncertain how to diagnose and may not even know to whom the patient should be referred for treatment.

Even experts in a given rare disease face challenges. Diagnostic criteria may be unclear or not fully established. Diagnostic tools and capabilities are often limited, as are treatment options. In some cases, the rare disease expert must be a bit of a trailblazer, trying to determine what is best for the patient with limited external support.

Pharmaceutical Companies

Companies that develop rare disease treatments must answer a fundamental question so they can make effective R&D investments: What is the size of the disease population? Given the rarity and relative isolation of rare disease patients, that question can be incredibly hard to answer. Very typically, the true epidemiology of a rare disease is unknown unless efforts will be made to study it more thoroughly.

When a company is unable to determine the number of patients to estimate the size of the market—and find the patients—it can cause a cascading range of challenges. These can include:

- Slow study recruitment

- Longer development timeline

- Delayed product launch

- Challenges in predicting resource requirements

- Slow commercial uptake

- Difficulty in realizing full commercial potential

Clearly, it’s in everyone’s best interest if pharmaceutical companies have tools and techniques at their disposal that can help them more effectively find rare disease patients.

Understanding the Patient Journey: A Key to Finding Patients

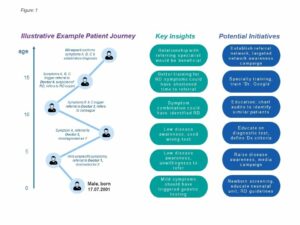

The first step in identifying patients is to understand the patient journey for a given disease. The patient journey can be defined as the typical pathway (or pathways) that patients go through from the first time they experience symptoms until they receive the correct diagnosis. By exploring the patient journey and “mapping it out,” pharmaceutical decision makers can identify the key obstacles that prevent patients from being diagnosed.

During the process of mapping the patient journey, several key questions can be answered (or the pathway to an answer can become more visible). For example:

- What were the typical disease symptoms?

- What specialties were usually involved in assessing the patients?

- At what point was the RD typically first suspected?

- Who most often established the correct diagnosis?

- How long does the journey usually take and what are the typical milestones?

- Where might we find undiagnosed patients?

- What were the key obstacles to diagnosis?

Mapping the patient journey can be a complex process that involves leveraging a range of resources and techniques. These can include:

- Secondary research (likely of limited value due to disease rarity)

- Primary research with patients / caregivers and patient advocacy groups (interviews or focus groups)

- Patient chart audits

- Review of patient databases or registries (often working with RD patient organizations)

Once the patient journey is mapped out, it becomes easier for decision makers to identify key points along the journey where interventions might make a positive difference in identifying patients more quickly and accelerating the time to proper diagnosis. Figure 1 shows a simplified example to illustrate this concept.

Examples of Patient Finding Strategies

While no two situations are identical, there are a range of interventions that pharmaceutical companies can use to find rare disease patients, more accurately size their markets, and help get treatments to patients. Some of these are briefly described below.

Centers of Excellence

Centers of Excellence (COEs) bring together multidisciplinary expertise in one place, serving as a locus for patient care, knowledge, and research in a disease state. They address the challenge of experts in a specific rare disease—or group of related rare diseases—being “too few and far between.” COEs can enhance their effectiveness by collaborating with referring networks of healthcare providers and by educating physicians about how to suspect, identify, and properly refer patients.

COEs and effective referral networks can represent a key strategy for patient identification. A pharmaceutical company operating in a rare disease market must identify the relevant COEs and develop a plan for engaging with them effectively. In cases where no COE exists, it may be possible to help establish one.

Awareness and Educational Campaigns

As mentioned, many rare diseases can go undiagnosed for years because patients and physicians fail to make the connection between the symptoms—or combinations of symptoms—and the disease itself. Awareness campaigns can raise disease awareness and educate patients, their families, and physicians about the symptoms and how to recognize them.

Patient-directed campaigns, typically using social media, disease awareness days, and advertising efforts can certainly help identify individual patients. This usually happens when parents, relatives, or other individuals are exposed to the campaign and make the connection between the symptoms described and a particular patient.

Over time, awareness campaigns—and physician-directed educational efforts—work to inform both physicians and patients. They raise general disease awareness, and can make the entire referral and diagnosis process far more efficient.

Some examples of these types of outreach efforts include International Gaucher Day, as well as various awareness campaigns and an educational website for Hunter syndrome.

Innovative Information Technology Solutions

With some rare diseases, the creative use of IT solutions can be used to aid physicians in identifying and diagnosing patients. As an example, computer-based algorithms such as IBM’s Watson are being used to augment and dramatically shorten the time-consuming process of rare disease diagnosis.

As another example, sufferers of DiGeorge syndrome and some other rare diseases will often exhibit specific phenotypic features, such as facial dysmorphologies, that can be identified by facial recognition software.

While the specific application of IT solutions will vary by disease state, it’s clear that smart-phone apps, artificial intelligence, and similar tools can represent valuable additions to the diagnostic armamentarium.

Bringing It All Together

To succeed in a rare disease market, a pharmaceutical company must become adept at finding patients. Often, that means developing educational materials, diagnostic tools, and other solutions to help patients and physicians more quickly recognize symptoms and associate them with the disease.

Doing this effectively requires a process that typically includes the following steps:

- Analyze: In this first step, it’s critical to understand the drivers for—and barriers to—diagnosis and patient origination. Mapping the patient journey is core to developing that understanding.

- Identify Options: Once the patient journey is mapped, decision makers can identify key leverage points along the way that might be ripe for intervention. After identifying those leverage points, the team must get creative about brainstorming and prioritizing potential strategies.

- Test: Before committing to any strategy at scale, it’s wise to pilot it in selected areas and evaluate the results. This will help identify those strategies that are most likely to work on a larger scale, as well as uncover needed refinements.

- Refine: The pilot process will expose gaps and opportunities for improvement. Before a full-scale implementation, it’s important to address those gaps and issues.

- Implement: Once the prioritized strategies and tactics have been pressure-tested and refined, they can be implemented at full scale. To ensure they deliver the desired results, the company must monitor and evaluate them on an ongoing basis.

Finding patients is critical for any company operating in a rare disease market. In fact, when we asked commercial decision makers about their challenges in rare diseases, finding patients was top on their list. To properly address this challenge, pharmaceutical companies must use a combination of process discipline and creative thinking.

Notes:

- Orphan Drug Report 2017, 4th edition, EvaluatePharma, February 2017, p. 3. Available at http://info.evaluategroup.com/rs/607-YGS-364/images/EPOD17.pdf

- National Institutes of Health, US National Library of Medicine. Huntington Disease. Available at http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/huntington-disease#statistics, accessed 4 May 2018.

- The Voice of 12,000 Patients. Experiences and Expectations of Rare Disease Patients on Diagnosis and Care in Europe. Available at: http://www.eurordis.org/IMG/pdf/voice_12000_patients/EURORDISCARE_FULLBOOKr.pdf

- Survey of the delay in diagnosis for 8 rare diseases in Europe (EURORDISCARE 2). http://www.eurordis.org/IMG/pdf/Fact_Sheet_Eurordiscare2.pdf, accessed August 20, 2013.