Introduction

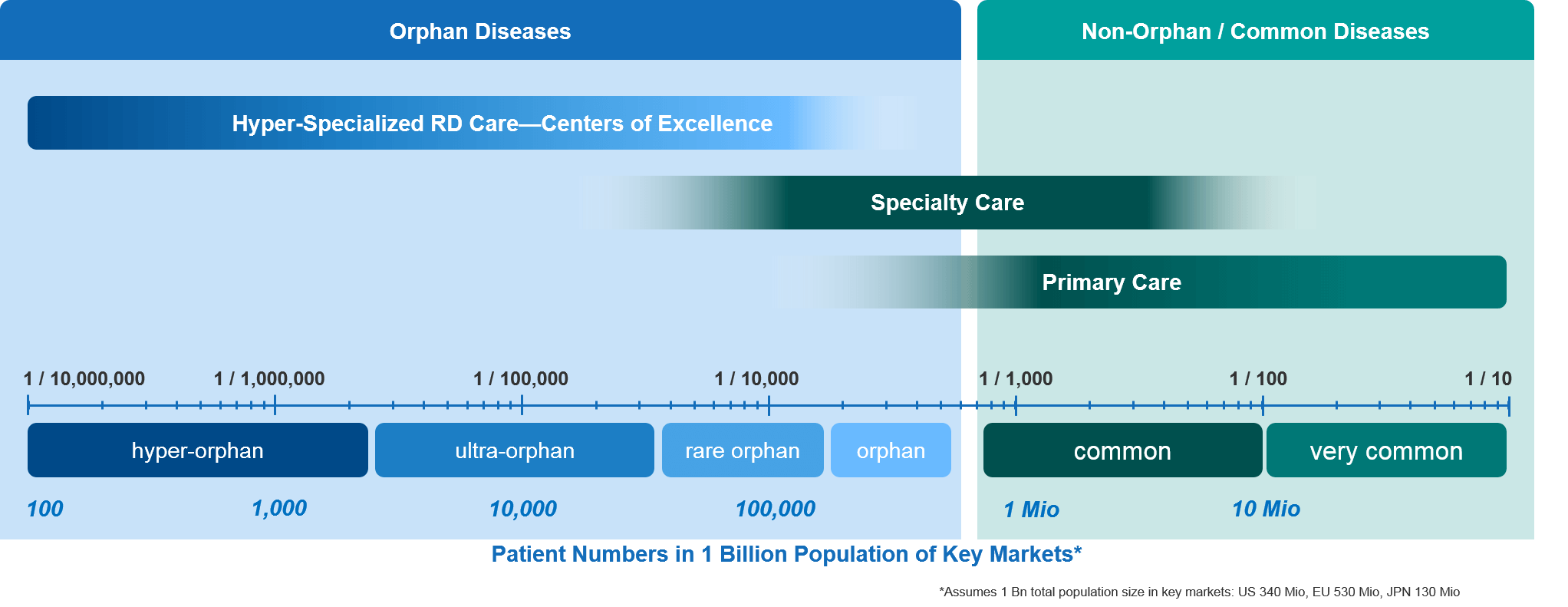

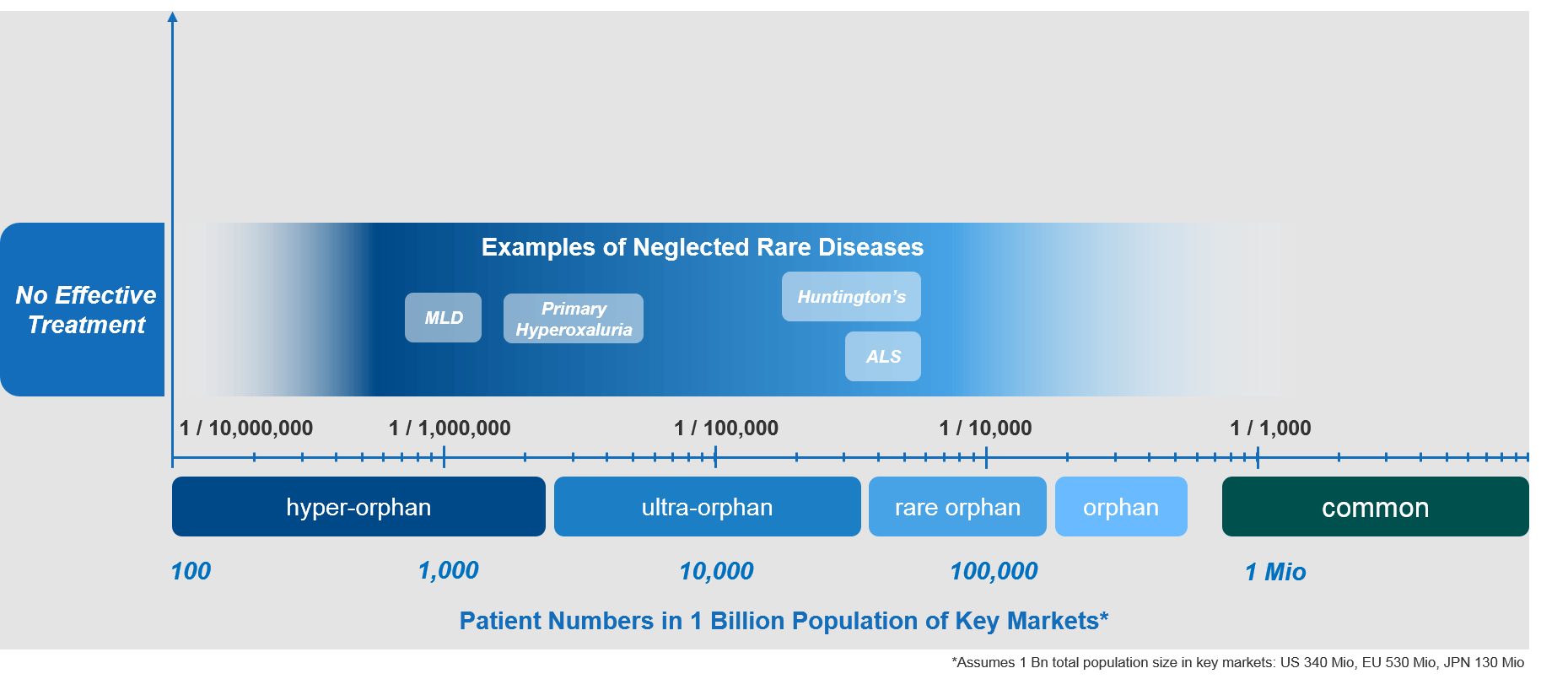

In previous articles, we explored several important aspects of rare diseases (RDs). First, we showed how different authorities define the term “rare disease” (or “orphan disease”). We also established a spectrum of rarity, ranging from those diseases that are considered common—with well-established treatment paradigms—to those that are “hyper-orphan,” affecting perhaps a couple of people in the entire world. In addition, we dug into how RDs differ from specialty diseases and the implications for biopharma companies who commercialize therapies to treat them. In this article, we focus fully on the rare end of the spectrum. In particular, we explore how “neglected” rare diseases differ from other RDs.

Of the total estimated number of rare diseases—about 7,000—only around 5% have an approved pharmacological therapy. Those that don’t are what we call here the “neglected” RDs, and they fundamentally differ from the few that have a therapeutic standard of care. Therefore, companies introducing novel therapies to treat those neglected diseases must have a different mindset and use different approaches.

Who Cares for Rare (From Specialty to Hyper-Orphan RD Care)?

In well-organized health care systems, the most common diseases are typically chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. They are generally recognized—and sometimes treated—by general practitioners as part of the primary (health) care system.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) typically suspect and diagnose these common diseases, quickly referring a given patient to the appropriate specialist for a more precise diagnosis and a personalized treatment strategy. These collaborative pathways between primary care physicians and specialists are quite established for well-known diseases, including rare oncology indications. As soon as a PCP sees a tumor-like condition, they immediately refer the patient to an oncologist.

The situation is different when it comes to much rarer orphan diseases. PCPs will typically be unfamiliar with a given RD. A PCP’s knowledge of a particular RD is likely to be very limited or—even more likely—completely absent. This isn’t surprising, as a PCP might never see a patient with a specific hyper-orphan disease throughout his or her entire professional career, given how few patients there are overall. Hence, the PCP is not likely to recognize the signs and symptoms to even suspect a diagnosis.

Further down the spectrum, even most specialists will be unable to recognize RDs that occur at a very low frequency, simply because they are so uncommon and so few patients exist. For the very rare diseases there are very few patients, and often even fewer experts.

With those very rare diseases, the collaborative referral pathways that are so well-established in common diseases simply do not exist. Patients usually have to live with their diseases for a long time until their conditions are suspected and finally diagnosed. After seeing many doctors and specialists over the course of many years, these patients often feel that no doctor is ever going to be able to help them. This can make them feel lost, desperate, and neglected.

As mentioned above, a small minority of RDs actually have effective treatment options, with focused care being provided within highly specialized centers of excellence (COEs). These COEs offer concentrated multidisciplinary expertise and plug into well-established referral networks from primary and secondary care. This, unfortunately, remains the exception to the rule.

Examples of Neglected RDs, Novel Therapies, and Their Market Situations

Some examples of neglected rare diseases include:

- Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD)

- (Primary) hyperoxaluria

- Huntington’s disease

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

All of these diseases are life-threating genetic conditions that lack effective therapeutic options to cure them or even slow their progression. Consequently, the standard of care for patients with these conditions is generally low, with a very high level of unmet need.

Thankfully, there are significant ongoing development efforts in all of the RDs mentioned above. Hopefully, those efforts will soon result in effective and badly needed therapies.

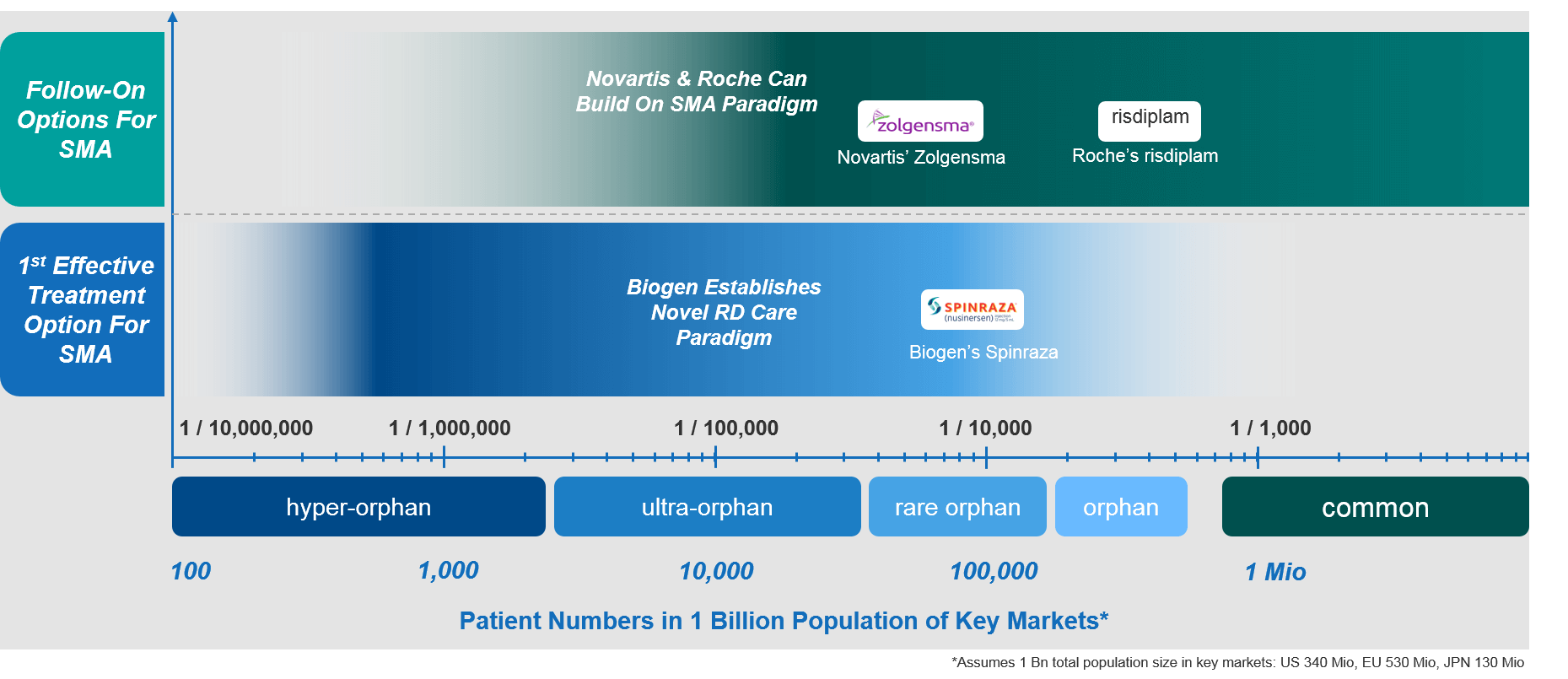

The SMA Example: What Changes When Treatment Options for Neglected RDs Become Available?

The introduction of a novel therapeutic option for a previously neglected RD can lead to very significant changes in the RD ecosystem. These changes can ultimately result in novel care paradigm(s) for that RD, as well as a dramatic improvement in the level of care for affected patients.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) provides an excellent example. SMA is a rare genetic condition that affects the neuromuscular system. The ongoing loss of motor neurons leads to progressive muscle wasting. The aggressive and rapidly progressing forms of SMA affect predominately infants and children.

Until 2015, SMA would have met our definition of a neglected RD with no effective treatment options available. That situation changed dramatically and rapidly when Biogen introduced Spinraza® (nusinersen) during 2016 in the US and 2017 in Europe. Spinraza® was and is a highly effective, disease- and life-changing treatment for SMA. It quickly became the standard of care for SMA patients.

Biogen’s significant efforts with Spinraza® completely transformed the outlook and the level of care for SMA patients. Today, there is a high level of SMA disease awareness. In addition, there is a network of dedicated centers of excellence (COEs) with deep SMA expertise and the ability to administer the drug intrathecally (i.e., directly into the spine). The way that SMA was being treated completely changed from pretty much doing nothing to dramatically augmented levels and quality of care. Importantly, these efforts resulted in life-changing outcomes for SMA patients.

The new level of SMA care described above made it a lot easier for Novartis/Avexis when they launched Zolgensma®— the first gene therapy for SMA—in 2019. SMA disease awareness, infrastructure, treatment paradigms, and COEs had already been established by Biogen.

Apart from the difficulty of introducing a novel gene therapy—with its own unique challenges—Novartis/Avexis did not have to define the SMA care paradigm and was able to build on what was already there. And thanks to Biogen and Novartis/Avexis, Roche will have an even better situation when it introduces risdiplam, its much simpler oral treatment for SMA, which is expected to be launched later this year.

With soon-to-be three highly effective treatments available to patients, SMA has come a long way from a neglected RD to a bit of a “hot spot” for biopharmaceutical companies in this area. The resulting high level of care is of course excellent news for SMA patients but it also illustrates well the gap and what patients with neglected RDs desperately need to have.

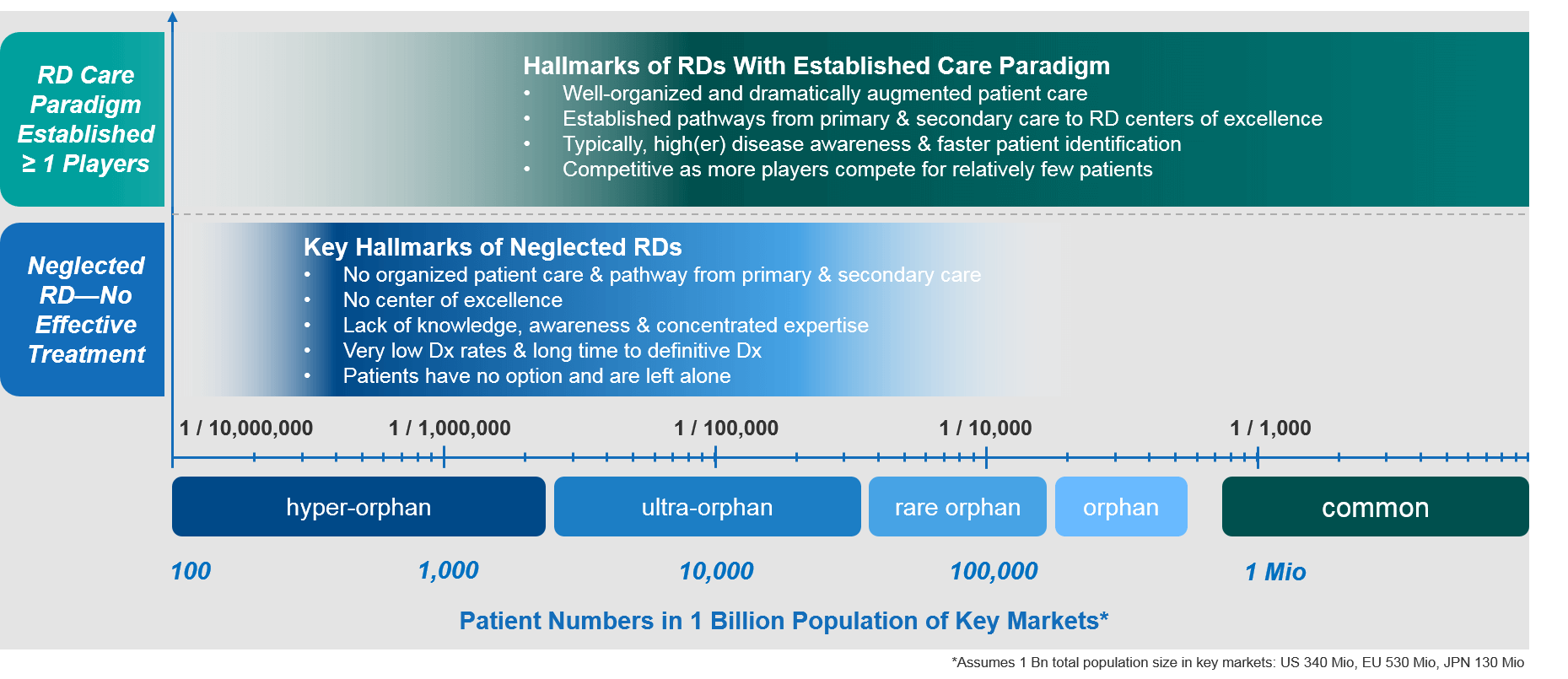

Implications for Biopharmaceutical Companies Launching Novel Therapies into RD Markets with an Established Treatment Paradigm

Biopharmaceutical companies who plan to launch the first and only effective treatment for a previously neglected RD will face significant challenges. First movers must direct significant resources to the goal of establishing the care paradigm de novo.

Examples of companies and treatments that have established an excellent care paradigm for previously neglected RDs are Biogen with Spinraza® (as previously mentioned) and Shire with Elaprase®, which is after many years still the only approved treatment for Hunter syndrome. An emerging example relates to primary hyperoxaluria, a neglected hyper-orphan RD that can lead to kidney failure. Currently, Alnylam is developing an innovative genetic treatment and will need to establish a novel care paradigm for hyperoxaluria pretty much from scratch.

In contrast, companies who are introducing additional or follow-on treatment options face significantly lower hurdles and can build on the already established paradigm. The key challenge facing these companies is largely of competitive nature—they need to competitively position their treatments against the established standard of care and align with the realities of the established paradigm and the specific market situation.

In addition to Zolgensma® and risdiplam, there are other good recent examples of novel RD therapies launching into established paradigms. These include Biocryst’s hereditary angioedema (HAE) drug berotralstat (BCX7353), as well as Apellis’ pegcetacoplan (APL-2). Both will launch into a well-established market with a clearly defined RD care paradigm and highly entrenched competition. Again, their key challenges will be to competitively position the novel treatment rather than establish the care paradigm.

Summary: Hallmarks of Neglected RDs vs RDs with Established Care Paradigms

In summary, there is a substantial difference between neglected RDs and those that have an established care paradigm. Neglected RDs are characterized by a lack of effective treatment options and very limited expertise available. This results in very low levels of patient care. Due to low awareness and lack of infrastructure and expertise, patients will have to suffer arduous, years-long journeys until they even receive the correct diagnosis.

A company that is about to launch the first effective treatment option for a particular RD faces significant challenges. It must establish centers of expertise, organize referral pathways from primary and secondary care to these centers, raise disease awareness, and identify the patients as early as possible so that they can benefit from the novel treatment. These first movers must expend significant resources to establish novel treatment paradigms de novo in an effort to help the highest number of RD patients get the best possible care.

In contrast, a company that launches a second or third treatment option for a RD faces quite a different set of challenges. Because many pillars of the treatment paradigm will already have been established, these companies must optimally position their treatment options against the existing care standard and future entrants. They’ll also need to identify those RD patients that will derive the most benefit from the novel treatment. In that sense, there situation is much more similar to a competitive launch in a specialty setting.

More treatment options for selected RDs is fantastic for patients as their quality of care improves and their options broaden. At the same time, the very large number of RD patients without options urgently need the same levels of attention and care. We have long way to go…