Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH, previously referred to as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH) is a disease characterized by excess fat accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis of the liver, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Despite increasing prevalence globally, in part driven by increasing prevalence of co-morbidities such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D), MASH has remained underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated.

Shifting guidelines and nomenclature, and the recent FDA approval of the first ever MASH-targeted therapy, has set up 2024 to be a catalyst year in the fight against MASH (note this recent FDA announcement). In this brief, we lay out additional challenges to clear for MASH development to take off in 2024 and beyond. As we move into the future of MASH treatment, we also lay out some considerations for manufacturers to help “futureproof” their development programs in an increasingly complex and competitive treatment landscape.

Understanding MASH: Diverse Causes and Significant Healthcare Burden

Often misleadingly referred to as simply a lifestyle disease, MASH, a severe form of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly referred to as NAFLD), can be caused by a diverse set of factors and impose significant negative impact on patients’ lives and burden on our healthcare systems. Clinically, diagnosed MASH can be stratified based on the degree of fibrosis of the liver, ranging from F0 (no fibrosis) to F4 (cirrhosis), with more severe forms of MASH incurring significant healthcare costs (Sheka et al., 2020). With the average healthcare cost of patients with MASH reaching ~$20,000 annually, patients with significant fibrosis (F4, or cirrhosis) can incur even higher costs, reaching well beyond $75,000 in cases where liver transplants are needed (Gordon et al., 2020). Of note, MASH is among the leading causes of liver transplant wait-listing in the U.S. and has been projected to increase significantly (Mazen et al., 2018), further compounding the impact of MASH on our healthcare system.

Driven by increasing rates of obesity, the global prevalence of MASH is expected to grow significantly over the next 10 years, in turn driving up the total cost and burden on healthcare systems around the world (Wai-Sun Wong et al., 2023). Thus, there is increasing focus on earlier detection and treatment of MASH. As a part of shifts in clinical practice, clinicians have continued to move away from invasive methods of diagnosis (i.e., liver biopsies) to support earlier intervention. So-called non-invasive tests (NITs), ranging from simpler blood panels to more involved MRI-based methods (Tincopa and Loomba, 2023), aim at avoiding costly and resource-intensive methods and speed up the triage and potential diagnosis of suspected MASH. However, with a wide range of testing options available, clinicians have had to rely on experience and judgement in selecting and sequencing NITs based on the historic lack of guidance on which test(s) to use and when. With the recent and emerging guideline updates, including from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), there is an ongoing push towards more streamlined guidance on test sequencing to establish a MASH diagnosis (Rinella, et al., 2023).

Following diagnosis, HCPs have had limited options to treat MASH, historically relying on lifestyle modifications and off-label medications to treat patients. The limited optionality of pharmaceutical treatments reflects the challenges manufacturers have faced historically while developing pharmacological treatments against MASH, with the space, perhaps rightfully so, often referred to as a “graveyard” for pharmaceutical development (Drenth and Schattenberg, 2020).

Recognizing the need to support development of MASH-targeted therapies, regulatory bodies (e.g., FDA and EMA) have provided draft guidance for accelerated approval to support development of novel therapies in MASH. Specifically, the FDA released draft guidance in 2018, outlining how Part H accelerated approval may be achieved for therapies targeting F1-F3 MASH (FDA Draft Guidance). In short, the FDA guidance outlines how either resolution of steatohepatitis or improvement in fibrosis, or a combination of the two, may serve as surrogate endpoints in F1-F3 patients. In contrast, draft guidance from the EMA requires achievement of both surrogate endpoints. Both FDA and EMA guidance, albeit with slight nuances, require long-term outcomes-based results (e.g., composite endpoints including progression to cirrhosis, reduction in hepatic decompensation events, change in MELD score, liver transplant, and all-cause mortality) to support full approval.

In sum, while approvals of pharmaceutical treatments of MASH were historically elusive, improved methods of diagnosis, an enduring unmet need for therapies, and enabling regulatory guidance all contributed to a sense of opportunity. In March 2024, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals became the first player to realize this opportunity, achieving both positive trial data and regulatory approval in MASH, with FDA approval of Rezdiffra (resmetirom) on March 14 – much to the excitement of patients and treaters alike.

However, Madrigal and the large body of other late-stage developers in the MASH space may face a number of additional challenges as they bring their products to market.

Key Challenges for Developers of MASH-targeted Therapies

Finding the Optimal Target, Route of Administration, and Combination Regimen

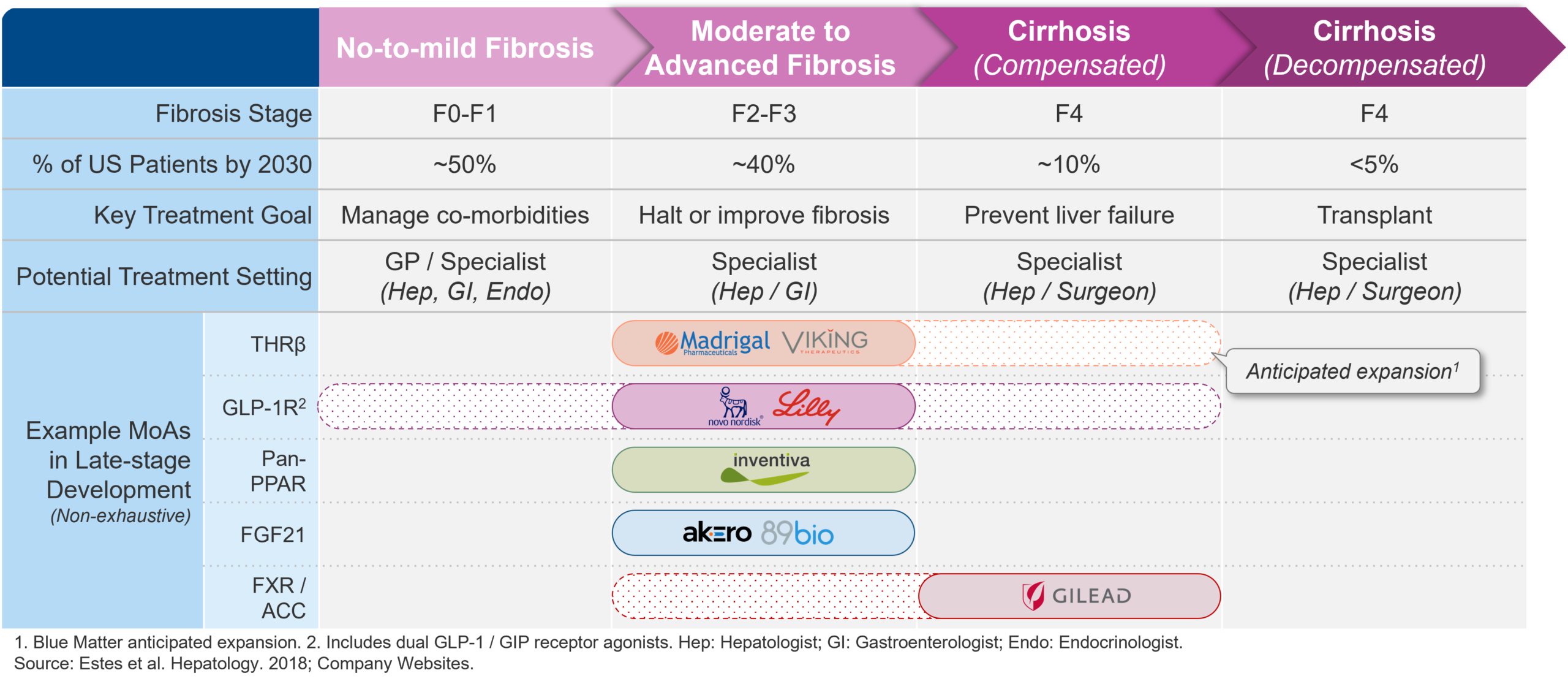

Navigating an increasingly crowded pipeline and vying for optimal market positioning, companies are opting for different targets, routes of administration, and combination partners. As evidenced by the many distinct mechanisms of actions (MoA) in development for MASH, manufacturers are pursuing a wide variety of different approaches. While clinical data on these different approaches continue to become available, the range of potential approaches with positive pre-clinical and early clinical data being tested in late-stage development suggest that there may be several viable options to effectively target MASH.

Figure 1 – Navigating an increasingly crowded pipeline and vying for optimal market positioning, companies are opting for different approaches.

At a high level, many late-stage assets may be classified as either (1) metabolic or (2) antifibrotic agents, albeit with some overlap. Additionally, several manufacturers are investigating combination therapies, aiming to achieve both resolution of steatohepatitis and improvement in fibrosis.

Metabolic agents aim to increase upstream metabolism to, in turn, reduce hepatic steatosis (i.e., build-up of fat in the liver). Agents in this category includes the recently approved thyroid hormone receptor β (THRβ) agonist resmetirom (Rezdiffra), as well as the well-known incretin mimetics semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound) from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, respectively.

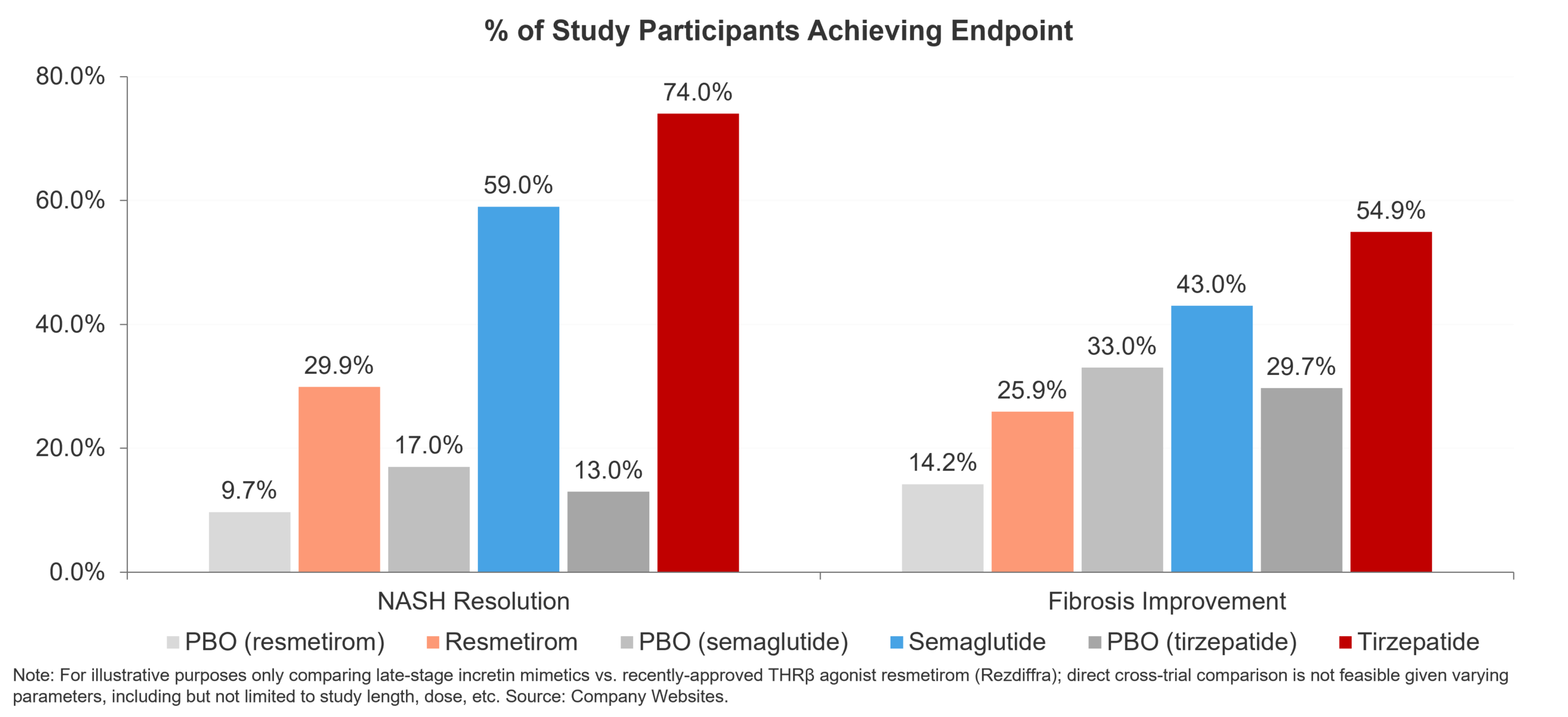

As the first-ever FDA approved MASH-targeted therapy, resmetirom serves as the proof point for metabolic agents in MASH. In the pivotal trial MAESTRO-NASH, the THRβ agonist displayed statistically significant improvements over placebo in both NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis (29.9% of resmetirom-treated patients vs. 9.7% of placebo-treated patients) and fibrosis improvement (25.9% vs. 14.2%) (Harrison et al., 2024). Confirmation of successful THRβ agonism in MASH came with the positive phase 2b readout of another the other late-stage THRβ agonist in development for MASH: Viking Therapeutics’ VK2809. Specifically, VK2809 boasted impressive NASH resolution (75% of VK2809-treated vs. 29% of placebo-treated patients) and fibrosis improvement (57% vs. 34%) data (Viking Therapeutics Press Release). While a pivotal trial is yet to be announced, these results likely put Viking on a solid trajectory as a next-in-class MASH therapy.

Turning to incretin mimetics, while there has been a continued flow of positive data specifically around the ability of these agents to reduce hepatic steatosis, most data has been less clear on improvement in fibrosis. For example, once-daily semaglutide (up to 0.4mg), while boasting robust ability to reduce steatosis (59% of patients on 0.4mg semaglutide reached NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis vs. 17% of patients in the placebo group), has shown limited impact on fibrosis improvement in mid-stage trials in MASH (43% in the 0.4mg semaglutide group vs. 33% in placebo group) (Newsome et al., 2020). Commenting on the available data to date, Novo Nordisk remain committed to evaluating semaglutide in MASH and are currently evaluating once-weekly (2.4mg) subcutaneous injections in the F2-F3 phase 3 ESSENCE study (NCT04822181), with readout of Part 1 scheduled for H2, 2024 (Novo Nordisk Q1 Report, 2024). In a sign of the potential ability of incretin mimetics to improve fibrosis, recent phase 2 data from Boehringer Ingelheim’s dual glucagon / GLP-1 receptor agonist survodutide, tested in F1-F3 MASH, demonstrated resolution of hepatic steatosis (83% of once-weekly survodutide-treated patients vs. 18.2% placebo-treated patients) (Boehringer Ingelheim Press Release). While encouraging, it remains to be seen how this plays out in any future pivotal trials for survodutide. Similarly, Lilly’s tirzepatide demonstrated robust improvements in both resolution of hepatic steatosis (74% of tirzepatide-treated patients achieving endpoint vs. 13% of placebo-treated patients) and fibrosis improvement (54.9% vs. 29.7%) in the phase 2 trial SYNERGY-NASH (NCT04166773) (Loomba et al., 2024). However, while there was a clear dose-response relationship seen for resolution of steatosis, no such trend was seen for fibrosis improvement. When taken together, metabolic agents are producing meaningful improvements in both resolution of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. Of note, with the emerging data on the ability of incretin mimetics to improve fibrosis, may warrant additional excitement in MASH.

Figure 2 – GLP-1RAs, despite impressive clinical efficacy, will likely settle as background or combination therapies in MASH in the near-term.

Antifibrotic agents, in contrast to purely metabolic agents, aim to reduce hepatic fibrosis and prevent further scarring. Antifibrotic agents in late-stage development include the FXR agonist cilofexor currently in development as a combination therapy with Gilead’s own firsocostat (ACC inhibitor) and Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonist). Similarly, Inventiva Pharma’s lanfibranor, a pan-PPAR agonist, may be viewed as targeting both upstream metabolism (via PPARα, δ, and γ agonism) and carrying antifibrotic characteristics (via PPARγ and δ agonism) and has produced encouraging phase 2 data to date, favoring lanifibranor for resolution of NASH without worsening of fibrosis (49% of lanifibranor-treated patients achieving endpoint vs. 22% of placebo-treated patients) and improvement in fibrosis (48% vs. 22%) (Franque et al, 2021).

Beyond mechanism of action and combination therapies, manufacturers are investigating opportunities to optimize dosing and administration, much akin to ongoing efforts to optimize tolerability among incretin mimetics used for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. With the current late-stage MASH pipeline containing both injectables and orals, one example of manufacturers looking to reduce dosing frequency is 89Bio. With their FGF21 analog pegozafermin, 89Bio are investigating reduced dosing frequency with subcutaneous injections of pegozafermin every other week showing similar efficacy as once weekly injections (Loomba et al., 2023). With patient and physician preference for more frequently taken orals vs. further apart injectables likely to vary, the current late-stage landscape contains a range of potential options for dosing and administration.

Identifying Target Physicians

Depending on the stage of disease, MASH may be treated by a range of different specialties. Patients with more progressed forms of MASH with fibrosis (i.e., F2-F3) are likely to be seen by hepatologists or gastroenterologists. As treatment goals shift and as novel treatment options come to market, it is possible that the treater base shifts; for example, to include a larger segment of General Practitioners. Pharma companies developing MASH assets should monitor these trends, as their customer-facing teams, marketing plans, and physician targeting efforts must account for the shifting treater landscape.

Ensuring Broad Access / Optimal Payer Management

With the emergence of MASH-targeted therapies, payers must critically consider which patients should be covered, for which therapies, and for how long (e.g., based on treatment guidelines, trial designs, inclusion and exclusion criteria, etc.). Payers will likely also have to consider how to navigate a “forever treatment” and are likely to look to emerging treatment guidelines, clinical trial designs, and product labels to inform coverage and reimbursement decisions. Of note, as MASH treatment diagnosis and management guidelines are likely to see significant shifts, payers may choose to consider appropriate starting, refill, and stopping criteria. Based on metrics reported in Madrigal’s Q1 earnings call, commercial payers are getting on board, with ~30% of commercial lives covered as of May, 2024 and with Madrigal expecting coverage of ~80% of commercial lives by the end of 2024 (Madrigal Q1 Results, 2024). However, in an example of how payers may choose to manage utilization of MASH therapies, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) announced that they will require diagnosis-based liver biopsy in order to prescribe Rezdiffra (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Formulary Advisor). This decision was made despite the USPI for Rezdiffra not stating any biopsy requirement (Rezdiffra USPI). With this in mind, 2024 is likely to offer additional insights into how access to MASH diagnostics tests and therapies will be managed.

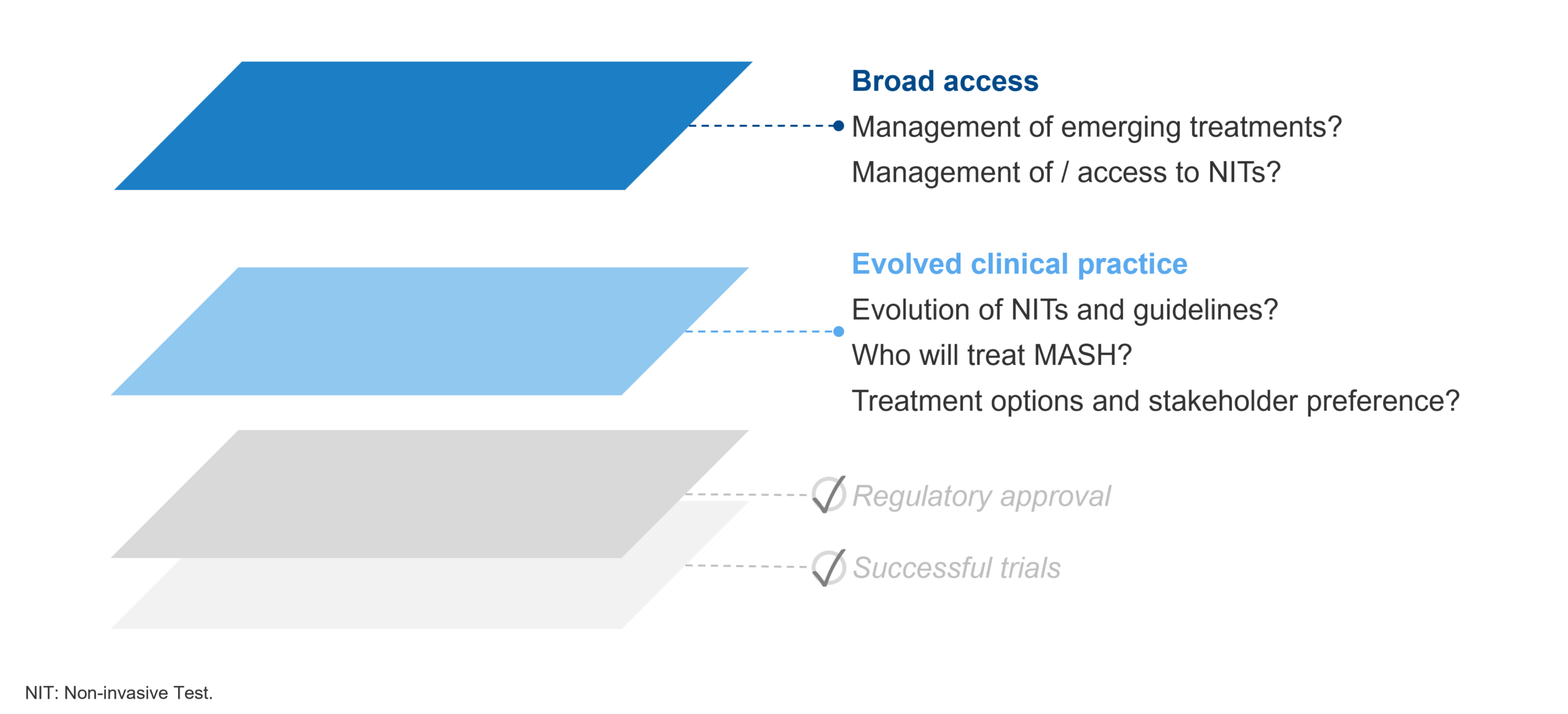

Conclusion

The successful trial and subsequent conditional approval of Madrigal’s Rezdiffra, rapidly evolving guidelines, and steady stream of positive data are reasons to be excited about MASH in 2024. However, it remains to be seen how clinical practice continues to evolve and coalesce around novel MASH-targeted therapies. This includes ensuring broad access is achieved to not only therapies, but associated diagnostic tools (e.g., NITs) to support earlier diagnosis and intervention. For recent and upcoming conditional approvals, it also remains to be seen how early successes and conditional approvals will translate to full approvals based on long-term outcomes data. Regardless, the first half of 2024 has set up the rest of the year to offer many important insights.

Figure 3 – Shifts in clinical practice and ensuring broad access will solidify 2024 as a catalyst year for the treatment of MASH.