In part 1 of this series, we provided an introduction to decision science (DS), offering a solid baseline understanding of the topic. In it, we do the following:

- Define what a decision is

- Contrast good and bad decision-making processes

- Define DS and its two interrelated branches: descriptive and prescriptive

- Describe some key areas within the biopharma industry where DS can be applied to help make better decisions

Here, in part 2, we continue our overview of DS, but we dive a bit deeper into the topic. Below, we introduce a decision-making framework, which we call Decision Path™. This framework ensures that decisions are in line with strategic priorities, more objective and bias-free, supported by the available information and data, and more likely to result in the desired outcomes.

We share this framework in a real-world context to make it a little less academic and a bit more tangible. Specifically, we describe it in the context of portfolio strategy development, which is a highly strategic and critically important area for most biopharma companies.

A Word About Portfolio Strategy

As we mentioned in part 1, Blue Matter recently conducted a series of one-on-one interviews with 14 biopharma executives and R&D leaders. The goal was to identify the key success factors (KSFs) that they think are essential for building a “Best Practice Organization” (BPO) in R&D. The research identified five key success factors, one of which was “smart risk-taking and decision making.”

Those R&D leaders articulated a common need to improve decision making when it comes to prioritizing investments across development-stage assets. Furthermore, they added that incorporating commercial and access insights—along with the patient’s voice—into the decision-making process is essential to success. In their minds, knowing when to kill a program is of paramount importance to avoid wasting time and resources that could be more productively applied to therapies that are more likely to add therapeutic and commercial value.

They also added that decision-making processes, depending on how they are designed, can encourage or stifle risk-taking. Some level of risk is desired, but it must be balanced by a data-driven assessment of the likelihood (and potential magnitude) of success, as well as the potential consequences of failure.

We found it interesting that, on this topic of decision making related to portfolio investment decisions, there was widespread agreement among R&D and commercial stakeholders. Both approached the topic from different angles, but the net result was the same: portfolio strategy development is an area where robust DS is needed.

Portfolio strategy is a critical nexus point, serving as a bridge between corporate strategy (which sets the overall direction for a company) and product or asset strategy (which identifies the most promising development and commercialization plans for an individual therapy). Figure 1 provides an overview of this bridging function.

Figure 1 – Portfolio Strategy as a Bridge Between Corporate and Asset Strategy

Portfolio strategy translates corporate strategy into concrete actions, whether by prioritizing R&D opportunities, allocating resources accordingly, or identifying critical gaps in the portfolio that guide business development (BD) activities. Because of its highly important role as a “strategic nexus point,” we chose portfolio strategy as a key area for the application of decision science. It’s certainly not the only area that can benefit from DS, but it’s a good one to use here for illustrating some key DS ideas and concepts.

The Decision Path™ Framework

While portfolio strategy operationalizes corporate strategy, it does not do so in a vacuum. It involves a diverse group of stakeholders with varying perspectives and preferences. And yet, they must make decisions that are aligned, tangible, actionable, and tractable. The key to ensuring alignment among these stakeholders is an effective and transparent process that they can leverage together. The Decision Path framework outlines the key success factors.

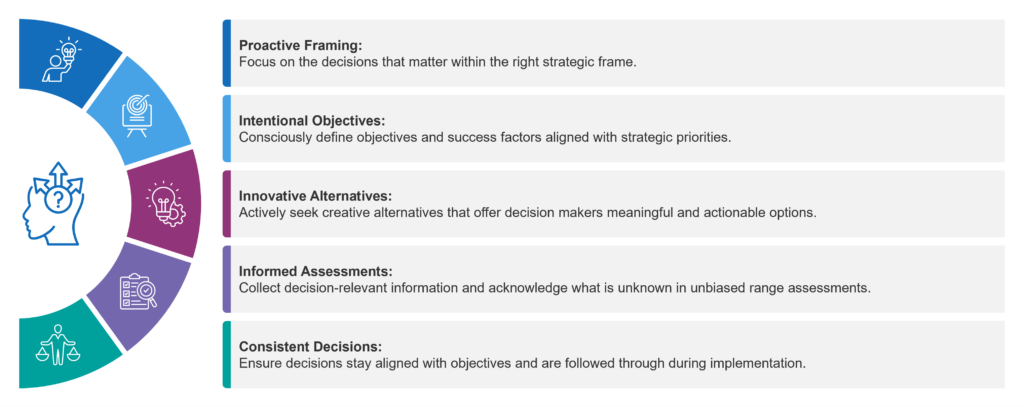

At a high level, the framework is an easy-to-understand mechanism that defines the principles of good decision making and integrates them into five critical elements. While the concept is straightforward, it can become more complex to apply in practice. This is because the various elements often require the use of psychology to understand human behavior—and tools and techniques such as back-casting, decision lensing and decision trees, as well as advanced analytical models, such as Monte Carlo simulation—to enable and enhance decision making.

Figure 2 – Key Components of the Decision Path™ Framework

In the following, we elaborate on these five elements within the context of portfolio strategy.

Proactive Framing

Proactive framing is intended to help teams align around the key decisions that need to be made by defining the right strategic context upfront. This approach reduces noise, clarifies what’s in scope, and ensures that efforts are focused on what matters most. It also supports shared understanding of which decisions have already been made and which remain open—helping teams avoid revisiting settled issues or overlooking critical topics.

Since decisions are rarely made in isolation, it’s important to identify the stakeholders whose knowledge, capabilities, or resources are essential to the process. For example, in the context of portfolio strategy, this means that all those involved – decision makers, portfolio managers, asset leads and asset teams – align on the decisions that matter within a clearly defined strategic context. This alignment minimizes distractions and clarifies the scope of work, enabling teams to concentrate on high-impact questions—such as how to accelerate growth in priority therapeutic areas through R&D investments or business development.

Intentional Objectives

Intentional objectives make corporate vision actionable. High-level ambition is translated into a concrete set of meaningful, measurable objectives that define what success looks like for a given decision. These objectives create clarity and consistency by ensuring that everyone involved shares a common understanding of what the organization is aiming to achieve. By building this transparent foundation, it prepares the ground for more focused and reflective decisions across the organization.

Within a portfolio strategy context, this ensures that individual decisions contribute to the broader strategic direction. It supports alignment across business units, functions, and geographies, reinforcing a connected and coherent decision-making culture. For example, an R&D portfolio might be guided by objectives such as “Increase the level of innovation”, assessed by the degree of novelty and potential for differentiation – ranging from incremental improvements and me-too assets to first in class breakthrough therapies. Similarly, “Leverage scientific and operational expertise” can be used and evaluated based on how effectively internal capabilities – such as proprietary platforms, a unique and leading scientific network or an existing commercial infrastructure – are leveraged and embedded in the portfolio. While these objectives may conflict (for instance, when pursuing new modalities without existing in-house knowledge) it becomes essential to have decision makers specifically address which objectives carry more strategic weight in light of the corporate vision.

Key guiding questions include:

- What does success look like in this context?

- Which objectives shape our decision?

- How should these objectives be prioritized to reflect our corporate strategy?

- How can each objective be observed, described, or measured?

- Are the objectives clear, relevant, and agreed upon by stakeholders?

This delivers three essential outcomes:

- Strategic translation – It connects corporate vision to tangible, context-specific objectives that inform action.

- Shared understanding – It aligns decision makers and stakeholders around a common set of goals, reducing ambiguity and minimizing hidden agendas.

- Assessable direction – It defines clear criteria for evaluating success, making decisions more structured, transparent, and consistent.

By identifying the right objectives—and only the right objectives—this ensures that future choices remain grounded in what truly matters to the organization.

Innovative Alternatives

Without competing choices or alternatives, there is no decision. With the desired outcomes in mind, what are the different potential ways of achieving them? Some may be relatively obvious, but it’s important to also be intentional about identifying innovative or unconventional solutions to explore.

Strategic decision-makers often operate with a broader perspective and greater risk tolerance than project leads, enabling them to consider bolder moves that may be outside the comfort zone of project teams. Encouraging this mindset helps ensure that the full spectrum of possibilities is explored—not just the most familiar or incremental options.

In the context of portfolio strategy, this could mean designing a set of alternate portfolios that each optimize for a different objective, such as innovation potential, aggressive growth, or operational expertise. These alternatives should all remain grounded in the company’s overarching strategic objectives, but differ meaningfully in how they seek to achieve them—ensuring the final decision is both informed and robust.

Informed Assessments

This element is all about evidence. With a set of feasible alternatives in hand, the team engages in a structured, objective evaluation of how each option performs against the defined objectives—without allowing preferences, opinions, or politics to cloud the process.

Informed assessments are grounded in data, not instinct. This element is about understanding—not deciding. It’s not about how much someone likes an option; it’s about how well each alternative meets the established objectives, based on observable outcomes and analytical rigor.

The element includes gathering all relevant information and clearly acknowledging what is unknown. Rather than oversimplifying or guessing, teams must explicitly represent uncertainty—whether through ranges, scenarios, or probabilistic tools like Monte Carlo simulations. This transparency around both what we know and what we don’t is critical for credible, comparable assessments.

In a portfolio strategy context, this means evaluating not just individual options, but how entire sets of assets or initiatives perform collectively. It involves modeling interactions, synergies, and constraints—while also applying benchmarks and external intelligence to ensure assessments are grounded in reality, not internal narratives. This serves to de-bias asset team assumptions by providing a neutral, portfolio-level view that aligns technical, commercial, and strategic perspectives.

Key questions to address include:

- How does each alternative perform against our agreed-upon objectives?

- What data supports that assessment—and where are the uncertainties?

- What assumptions underpin our analysis, and how sensitive are the outcomes to those assumptions?

- How do we compare alternatives on a common basis, using consistent metrics and methodology?

This delivers three critical outcomes:

- Analytical clarity – It replaces intuition with structured, evidence-based evaluation

- Transparency under uncertainty – It reflects knowns and unknowns honestly, avoiding false confidence or hidden risks

- Stakeholder alignment – It creates a common understanding of how alternatives perform, independent of preference or position.

By rigorously and transparently assessing how each option delivers against the organization’s goals, this builds the foundation for clear, credible, and unbiased decisions.

Consistent Decisions

After assessing the various alternatives, decision makers must choose the pathway that best aligns with their objectives and strategic priorities. While the earlier elements were more about structuring and preparing the decision transparently, this is the point where choices are made—grounded in rigorous analysis and informed by clearly defined priorities.

The decision should reflect how well each alternative performs against agreed-upon criteria, while also taking into account the relative weighting of objectives—such as a preference for innovation versus proven expertise. For instance, commercial leaders may favor bold, high-growth opportunities, while R&D leaders may prioritize technically robust, lower-risk approaches. Ultimately, the final decision should be consistent with the organization’s strategic priorities, such as its risk tolerance or emphasis on innovation.

In the context of portfolio strategy development, this might involve selecting a portfolio of assets that best advances strategic objectives, allocating resources accordingly, and communicating the decision—and its rationale—clearly across the organization. A transparent, disciplined approach not only strengthens consensus but also increases the likelihood of delivering strong, sustained outcomes.

Conclusion

When leveraging any decision-making framework, it’s important to keep a few guidelines in mind. First, focus on the decision, not the outcome. Good decisions are made based on the best available information, a clear set of objectives, and thoughtful processes. They should be evaluated in the context of what was known and knowable at the time—not in hindsight. This distinction allows organizations to learn, improve, and act with confidence, even in the face of uncertainty.

Second, embrace real alternatives. A decision without choice is not a decision. Deliberately generating and exploring a range of feasible options—rather than defaulting to a pre-selected path—opens space for innovation and reflection. It also helps to distinguish what an option currently is from what we wish it to be, a distinction that is crucial for honest assessment and productive iteration.

Third, build transparency into every layer of the process. Separate facts from assumptions. Be explicit about what is known and what is uncertain. Assess alternatives against clear objectives, and understand how different decision-maker preferences influence the path forward. By illuminating these dynamics, teams foster alignment, reduce misinterpretation, and unlock commitment to action.

And finally, use psychology to overcome bias. Decision-makers should be cognizant of their own biases and the common ways in which bias can be injected into a decision-making process. Recognize that perfect information is unattainable, focus on what can be controlled, and leverage behavioral science to make rational decisions. In the end, the power of this framework lies in creating clarity, accountability, and direction.