If the leaders of an emerging biopharma company plan to commercialize their development-stage product(s), then they obviously must understand what capabilities, activities, and resources will be needed to commercialize successfully. But what about a company that has chosen a different strategic path? For example, does a company that plans to out-license a product to another entity also need a solid understanding of what it will take to commercialize? The short answer: yes.

This article is part of our ongoing series, 7 “Make or Break” Factors for Emerging Biopharma Companies. Here, we address Factor 4: Knowing What It Will Take To Commercialize. We explore why every company—regardless of corporate strategy—needs to know what will be required to commercialize their product(s). We also identify some of the best practices and potential pitfalls as they define commercialization requirements.

Importance Of Understanding Commercialization Requirements

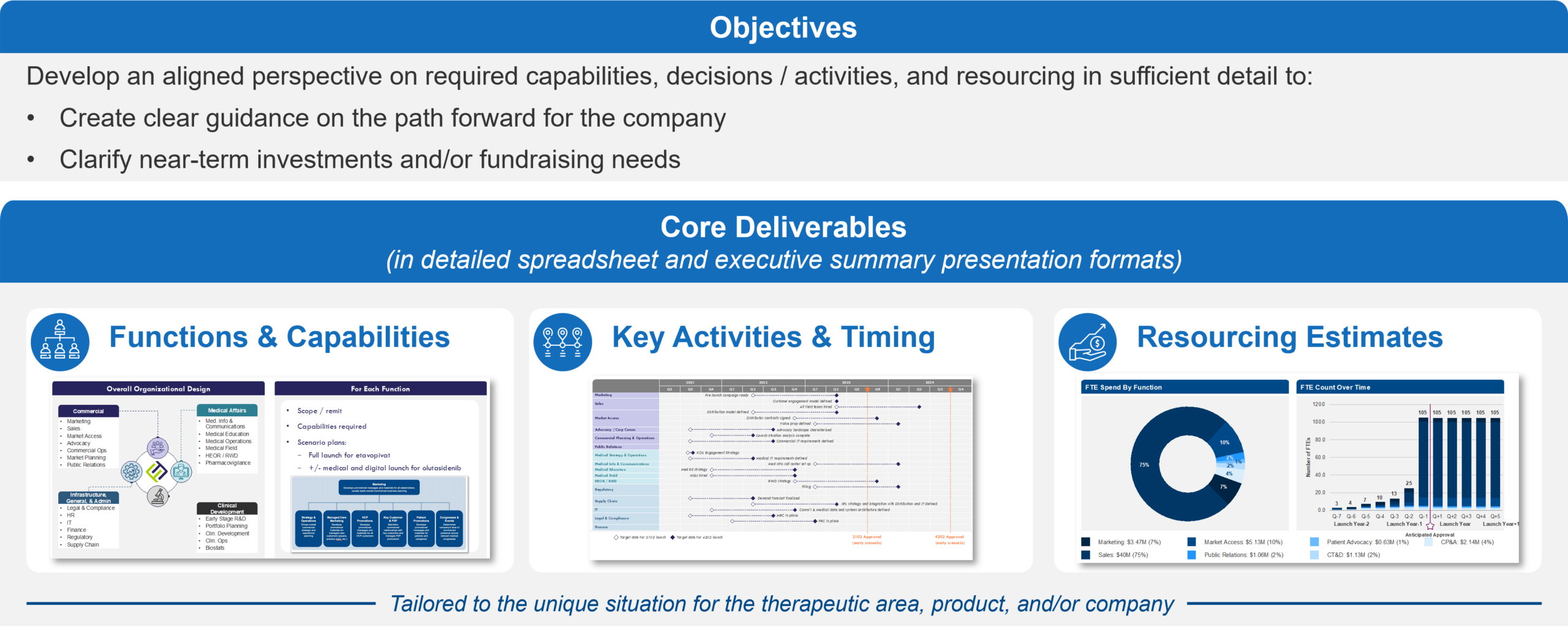

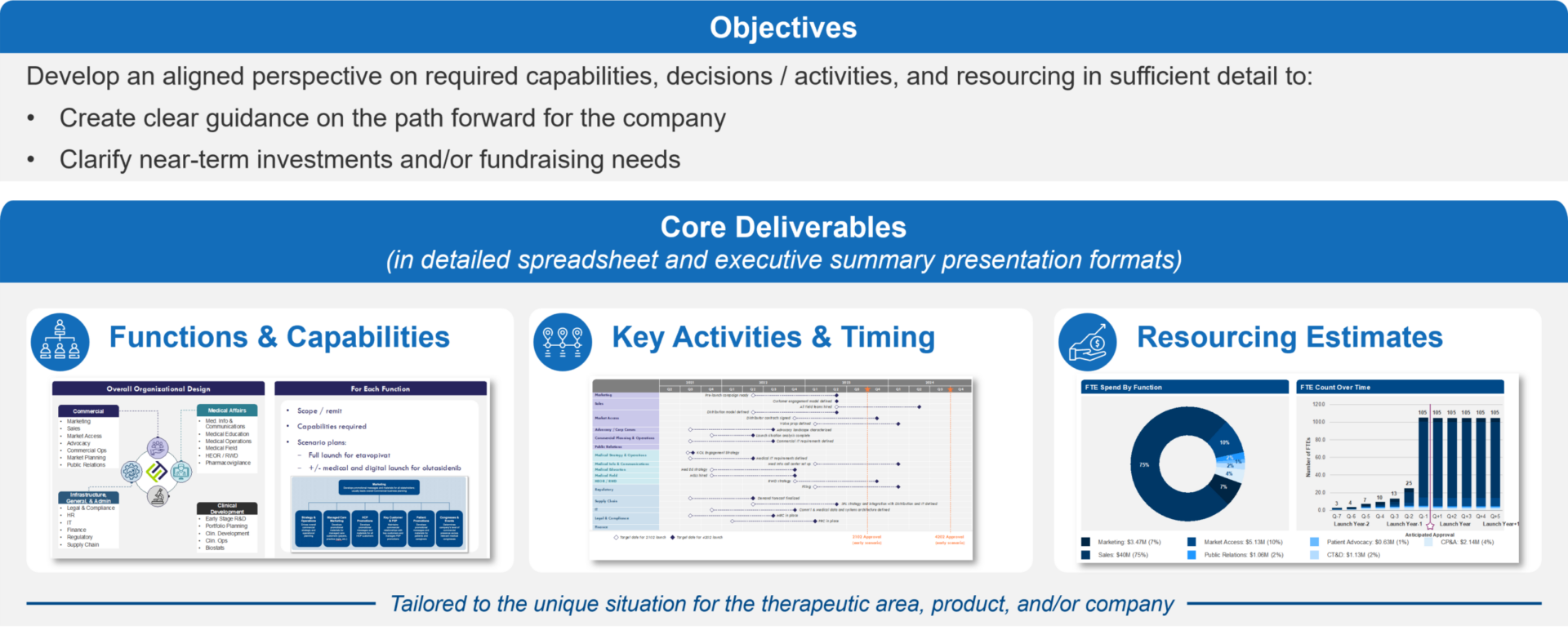

Figure 1: Overview of Commercialization Requirements; Focusing on what needs to be done and when

When we talk about “what it takes” to commercialize a product, we generally refer to three main components:

- Required Capabilities, with a focus on the functions that must be built or evolved and their scope / remit

- Roadmap of key activities / milestones and approximate timing

- Resourcing, including the approximate budget and full-time equivalent personnel (FTEs) required to execute against the Roadmap

Understanding these requirements early will create value for a company regardless of its overall corporate strategy, with specific benefits for different approaches:

- A company that doesn’t know their preferred path forward can inform its decision to go alone vs. partner vs. out-license by better understanding what would be required for each option (more on this in Factor 5: Choosing The Best Path Forward)

- A company that plans to go alone can define a clear path forward for the organization and inform required fundraising

- A company that plans to partner can gain a better understanding of what should be kept in house, and in which geographies, as well as the capabilities needed from a potential partner

- A company that plans to out-license can become better equipped to navigate discussions on potential deal terms and the relative value vs. the investment required to launch its product

Before beginning a detailed assessment of what will be required, a company should develop an understanding of the internal and external context, including:

- [If known] The company’s overall corporate strategy – specifically whether the company has clear aspirations to commercialize, and if so, in which geographies

- The company’s vision for the product, including how that fits into the corporate strategy

- Key issues the product will face at launch (informed by Factor 2: Generating the Most Important Customer Insights Early)

Commercialization Requirements

Required Capabilities

Launching a product for the first time is complex. Companies preparing for their first launch must simultaneously shape the product and market while also building the organization, including scaling up teams and infrastructure.

However, leaders of emerging companies don’t always grasp the full scope of the task they face. Leaders who have focused on discovery and clinical development are often not aware of the breadth and complexity of commercial functions and why each is required. Conversely, leaders who have only launched before in large pharmaceutical companies may be aware of the importance of commercial functions in shaping the product and market, but may underestimate the full scope of new infrastructure that needs to be built as a company transitions from clinical stage to commercial stage.

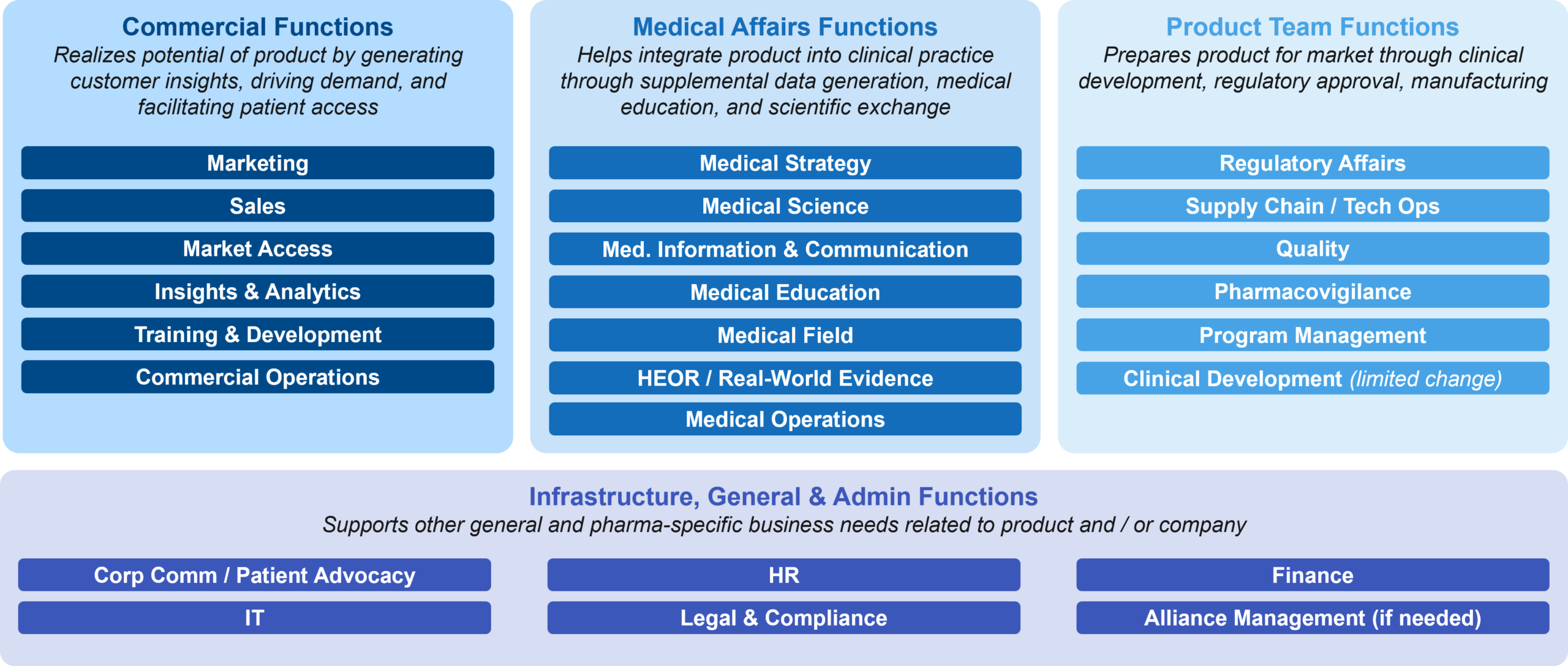

Figure 2 provides a brief summary of the typical functions that must be built or evolved in preparation for a company’s first launch:

Figure 2: New or Enhanced Functions for Commercialization

Some functions and capabilities will need to be designed and built from scratch, such as Marketing and the underlying Brand and Launch Planning capability. Others, such as Finance, HR, IT, and Legal / Compliance, may already exist and will need to build additional capabilities for a commercial stage company.

In short, leaders need to carefully assess which capabilities and functions must be built vs. evolved, and how. Leaders should not underestimate the time, effort, personnel, and funding that will be required to do so, which leads into the next two commercialization requirements: developing a roadmap and ensuring the proper resourcing.

Roadmap

Once a company knows the capabilities it needs to build, it must develop a “roadmap” of milestones and activities to get there. Building an effective and right-sized roadmap could take up an entire article series on its own, so we will focus on the most common learnings from our experience.

One of the most common pitfalls is starting too late. While established companies with existing infrastructure typically start planning about 2 years before a potential approval, emerging companies without this infrastructure should begin planning around 3 years before approval to give enough lead time to build infrastructure and execute launch readiness activities for the first time.

A second learning focuses on striking the right balance about when to initiate key activities. There are two viewpoints that must sync up: (1) working backwards from the anticipated launch date to determine the optimal start date for key activities based on anticipated lead times, and (2) smartly choosing clinical and regulatory milestones to trigger the initiation of key activities. Ideally, a company can take a thoughtful approach to starting certain parts of key activities “at risk” – and if not, to understand the tradeoffs (more on this in the discussion on resourcing below).

The third learning is to ensure the activities in the roadmap will address the key issues the product will face at launch. Many times, an emerging company will leverage an existing roadmap. However, a roadmap used by a larger pharma company won’t reflect the realities of a leaner first launch. Conversely, roadmaps used by other small biotechs may not fully reflect the same key issues and conditions.

Finally, in an ideal world, roadmapping is an iterative exercise, starting at a high level that focuses on key milestones, then moving progressively into more detailed activities over time. Companies that don’t start early enough at a higher level risk finding themselves falling behind and not having enough lead time to prepare for launch with high enough quality.

Resourcing

If a company does a good job defining the required capabilities, activities, and timing, then defining the required budget and FTEs should be relatively straightforward (though not necessarily “easy”). However, there are a couple of important watchouts.

The most significant pitfall involves failing to understand the tradeoffs associated with different resourcing philosophies. In many cases, clinical-stage companies tightly manage the quarterly spends, and when they see the magnitude of investment required to commercialize, they often aim for a lean and gated approach to resourcing. However, over-optimizing on the lean and gated approach can come with significant tradeoffs, including not being fully ready to launch at approval.

There are situations where this approach makes a lot of sense, specifically when there is significant risk that the product will not be approved. Consider an example in which a company is developing a product with a challenging safety profile that an FDA Advisory Committee supported with a slim majority. In this situation, a company may want to delay the significant investment of hiring a sales force until after the product is approved. The clear tradeoff in this case is that the company will lose months while ramping up the sales force after approval, which might result in a delay in sales revenue (or potentially even a lower peak revenue if the market is highly competitive). Although the tradeoff may make sense in this situation, expectations on the implications should be clearly set across internal teams, leadership, and the board of directors / investors.

In another real-life example, one company balked at the investment required to develop a full data warehouse with analytics capabilities, instead choosing to invest in a “leaner” option of a simpler database. However, once the product was approved, all the reporting—including sales reports, reports for the executive team, and reports for investors—required two FTE to continuously analyze data and develop reports that could have otherwise been automated. Furthermore, these two people were not able to perform their core responsibilities since all their time was spent working on reports. In hindsight, this decision ended up costing the company more (both in money and time) than the initial investment.

Another common pitfall is underestimating the time required to effectively build out functions. Building an effective commercial team starts with hiring the right leaders and then allowing them to further hire the rest of their teams. All of this requires sufficient lead time to search for, interview, hire, and onboard leaders and then the rest of their teams.

To make these types of tradeoff decisions, leaders can analyze analogs to understand what other companies have done. It’s important to note that such analogs, while useful, are not infallible. Every company and situation is different, so leaders should resist the temptation to look at a couple of analogs and just “lift and shift” those approaches to their own situations.

Coming Next

Throughout this article, we’ve focused on knowing what it takes to commercialize. But how does a company leverage this work to decide whether to commercialize a product on their own vs. partner vs. out-license—and in which geographies?

In our next installment, we’ll explore how companies can remove some of the confusion surrounding these decisions. In particular, we’ll discuss how leaders can avoid leaving bad options on the table for too long, reduce their available paths forward to a manageable number of viable options, and avoid the organizational swirl that sometimes affects companies in this situation.