The Digital Therapeutics (DTx) space is new and rapidly growing within the healthcare landscape (for a DTx 101: Intro and Overview, see here). Biopharma companies should carefully consider their potential entry into this space, as their customers will be increasingly engaging with DTx products that have the potential to complement or even compete with biopharma products. That said, while there are potentially significant opportunities for biopharma companies in DTx, there are also uncertainties and potential challenges which differ from the more “traditional” biopharma space.

Here, we explore these challenges using the real-world example of the sleep improvement DTx market, with focused attention on patients with chronic insomnia. This is a particularly informative example because of three reasons: (1) the products we highlight represent the three most common approaches to DTx commercialization (see Table 1), (2) the fundamental therapeutic intervention of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is relatively undifferentiated between the products, making their expected clinical impacts similar, (3) the pricing expectations and resulting market potential are vastly different for each product. Ultimately, an interplay of regulation, access, price, and underlying clinical data generates complex market dynamics.

While the market is still young, we believe chronic insomnia may be an eventual case study for non-prescription digital therapeutics (NDTs) and wellness apps eating into the market for prescription digital therapeutic (PDT) products. This is a risky situation that biopharma companies need to understand—if not at times avoid—if their strategy is to develop prescription digital therapeutics.

Below you will find a brief overview of the chronic insomnia market, commentary on the DTx competitive dynamics, and finally, a discussion of the general approaches for biopharma companies to mitigate the risks and challenges as they decide which DTx markets to enter.

Overview of the Chronic Insomnia Market

Anyone who has ever had a series of sleepless nights knows that insomnia is a frustrating condition with a major impact on quality of life. Approximately 25% of Americans develop insomnia each year, and while about 75% recover, the remainder do not and begin experiencing chronic insomnia. For these individuals whose insomnia persists and becomes chronic, the need for effective treatment is very high.

Pharmaceutical interventions (i.e., “sleeping pills”) may be helpful for transient insomnia, but for chronic insomnia, the risk of side effects, issues with drug tolerance, and / or drug dependence is high enough that other methods of treatment are preferred. In fact, for chronic insomnia, the typical recommendation for first line treatment is CBT-I, which has been widely studied and accepted as an effective intervention.

CBT-I is a program of psychological and behavioral interventions where the participant learns various tools to recognize and change beliefs and behaviors that reduce the anxiety associated with insomnia and improve sleep quantity and quality. CBT-I can be quite effective, but a major challenge is supporting participants in learning and maintaining the program over time.

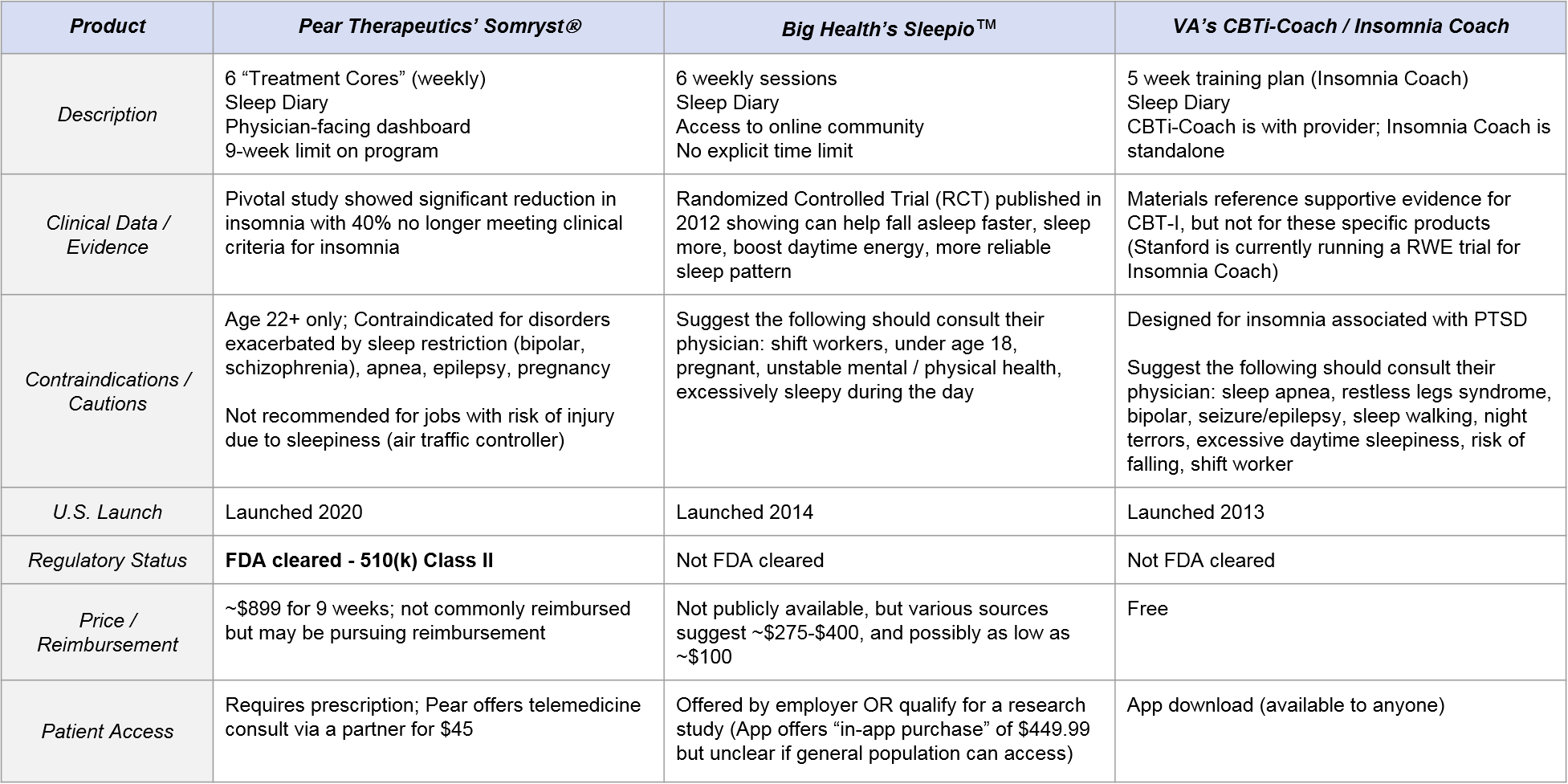

Classically, this is done via close interactions between the patient and a therapist (or other clinician experienced in the methodology), but this level of care is not feasible for many patients. Three main DTx products have emerged to address this gap by supplementing or as an alternative option to clinician delivered CBT-I: the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA)’s CBT-i Coach and Insomnia Coach, Big Health’s Sleepio™, and most recently, Pear Therapeutics’ Somryst®. All three products are app-based and offer a similar program of CBT-I including elements of sleep education, sleep restriction, sleep hygiene, and a sleep diary for the user to track progress and outcomes (See Table 2).

However, they differ significantly in terms of product strategies and business model:

- Somryst is the only FDA-cleared option. It is high-priced (but potentially pursuing reimbursable status) with robust clinical evidence, requires a prescription, and is intended to be under the supervision of a health care provider. Notably, it has an indication specifically for “chronic insomnia.”

- Sleepio has clinical evidence but no FDA label, is only available via employers (who likely pay ~$100 – $400), and the program is intended for stand-alone use (no physician engagement is specified other than for certain contraindications). Big Health describes the product as for use with “poor sleep” and often avoids directly using potentially regulated claims around “insomnia” or “chronic insomnia” though its studies are in patients with clinical insomnia.

- The VA’s CBT-i Coach and Insomnia Coach apps do not have direct evidence of clinical efficacy. They are free and accessible to anyone, although they are designed for individuals suffering from insomnia related to PTSD. CBT-i Coach is to be used with healthcare provider oversight, whereas Insomnia Coach is for “self-help”.

Competitive Dynamics: Higher-Priced Prescription Models vs. Lower-Priced “Unregulated” Models

Because the three competitors have such distinct product strategies with associated opportunities and constraints, the competitive interplay is complex. Below we will discuss some of these dynamics to highlight some of the learnings we have gathered by working in this space for several years. As you read, keep in mind that we believe both PDT and NDT models can have substantial commercial potential as long as a company brings the right product and strategy to the appropriate market. The question is what type of market will chronic insomnia become?

Regulation

The decision to pursue regulation (as Somryst has done) is a “high risk, high reward” approach, as it certainly delays market entry, hampers product development agility thru oversight requirements, and carries the risk of regulatory failure. That said, if regulatory clearance is achieved (as it was for Somryst), then they can try and leverage this as a differentiator vs. other products that cannot claim the same regulatory greenlight.

However, in our experience assessing the “value” of FDA clearance is not always straightforward and should not be assumed to be a strong differentiator yet. Notably, Somryst achieved a Class II 510(k) pathway clearance using their own Pear reSET as the predicate. This strategy leans the clearance on risk and safety more than efficacy, and payers and physicians know this. We’ve often heard that “it won’t hurt”, however it may not help either without demonstrating in a real world setting that the product delivers clinical and economic value.

And all the while that Pear is seeking regulatory clearance in this example, Big Health has nearly a 6-year head-start on developing customer relationships (see CVS Caremark Digital Formulary inclusion), demonstrating real world value, and rapidly developing its product outside of regulatory oversight. So, only time will tell what extent the “medical claim” matters in digital therapeutics.

Clinical Evidence

Perhaps unsurprisingly as it is a free app and the CBT-I methodology itself is quite validated, the VA’s CBT-i Coach / Insomnia Coach does not offer any direct clinical evidence for its efficacy (claiming only that “CBT-i Coach is based on the therapy manual, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Veterans.”). Conversely, both Somryst and Sleepio have published “gold standard” randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for their products.

Sleepio’s first publication is now almost 10 years old, suggesting that their choice to not pursue regulatory clearance based on this data is perhaps seeking to split the difference between:

- FDA labeled clearance (and the associated time and effort costs to achieve it, as well as access restrictions as compared to remaining unregulated) and

- Sufficient clinical data to allow customers to comfortably choose their lower-priced product.

For further information and analysis of Sleepio’s clinical evidence dig into NICE’s 2017 Medtech Innovation briefing. But also noteworthy, is that Sleepio has been used in real world settings for years and likely leverages that data in contract discussions. For instance they have a completed study supporting $1,667 in healthcare cost savings – which is in a language that decision makers particularly like.

Somryst has a very robust set of clinical studies showing reduction in insomnia severity, durability up to 12 months and even some effects on depression that are a compelling start for payer and clinician discussions. Most of the evidence is based on the historical “Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi), an early version of Somryst with equivalent content.” We’ve found that while on paper, the product looks good, there is healthy skepticism of its real world translation and whether patients will act similar to how they did in the controlled settings.

Customers

The Chronic Insomnia market is an especially interesting arena as the key customer for each product is different:

- For Somryst, it is the patient and / or their HCP who recognize chronic insomnia and seek to treat it using a “traditional” prescription-based intervention approach. The primary interest for them would be demonstrated clinical efficacy and safety in treating a diagnosed condition of chronic insomnia.

- For Sleepio, it is employers who make the choice to offer this product to their employees (independent of any HCP relationship). The primary interest for them would demonstrate benefit in work-related outcomes, e.g., improved efficiency, less time off.

- For CBT-i Coach / Insomnia-Coach, the customer is a subset of chronic insomnia patients, namely US veterans with PTSD who are directed to the product by the VA. The primary interest for them is also clinical benefit, but we expect them to also be price-sensitive (e.g., interested in trying a free version first). While the app is technically accessible to anyone, it seems likely that the majority of users are this demographic.

While these customers are technically different, they are related through a given patient’s journey whose implications we will talk more about in the section on access and adoption.

Pricing

In this market, we see an extremely wide range of pricing, from Somryst at $899, to Sleepio at anywhere from $100 – $450 (low is based on employer benefit discount estimates and the high as an in-app purchase option), to the free CBT-i Coach / Insomnia Coach.

Somryst’s challenge is to establish a compelling value proposition for insurers to figure out a coverage, coding and benefits approach given its significantly higher price from its competitors. Their approach has been to lean on clinical data and their stand-alone FDA clearance status. A win for Somryst would be similar to drug coverage negotiations, where the end-user has little to no out-of-pocket cost, which would put it on a similar competitive position to Sleepio. But simply based on the pricing above, is Somryst’s advantages worth a potential 2x price increase?

Access and Adoption

Because the business models and target end-users are slightly different, and because Somryst is a regulated prescription, the range of access ease is extreme:

- Somryst is challenging to access as it requires a prescription as well as payer reimbursement to avoid the high price tag for an out-of-pocket approach. Currently, the adoption of payer reimbursed digital therapeutics is low to near non-existent. Pear Therapeutics’ has been working on this barrier for years through its PDT portfolio products reSET® and reSET-O®. Via its recent SPAC merger (with a nice $1.6B valuation), the SEC filings noted that Pear is targeting revenue of $4 million, $22 million, and $125 million in 2021, 2022, 2023 respectively. Some nice sleuthing from Brian Dolan at Exits and Outcomes indicates that Pear had 3,370 reSET-O users between August 10, 2020 and April 30, 2021. In addition, they had 812 reSET users between August 10, 2020 and April 30, 2021. Both numbers demonstrate that access and adoption challenges remain for the PDT pathway.

- Sleepio access is moderately challenging, as individuals cannot easily get it directly. It is primarily available via employers at no out of pocket cost. However, from an eligible employee perspective, the access and adoption is relatively straightforward as the employer is highly-motivated to provide this product to help employees to regain productivity lost to poor sleep and insomnia.

- CBT-i Coach and Insomnia Coach are quite easy to access. They only require an app download. Furthermore, Insomnia coach is commonly found in the top results of Google with the terms “insomnia app” whereas of this writing, neither Sleepio nor Somryst are listed on the first page.

One thing to keep in mind about the end-user that is targeted via these different business models is that individuals progress through “poor sleep” to “acute insomnia” and eventually to “chronic insomnia”. So while they may be targeting different end users, it’s reasonable to assume that an individual may already have experienced and failed with Sleepio during their acute insomnia phase, which could dampen their interest in a similar therapeutic approach in a later “chronic phase” without compelling evidence of its effectiveness. So this is why we suggest that the Sleepio NDT may be “eating” Somryst’s PDT market by reducing the overall eligible and interested chronic insomnia patient population.

Marketing

Given the differences in key customers and product attributes described above, each competitor must consider the appropriate marketing strategy. Big Health targets employers (supposedly with a minimum in the single thousands of employees) through a B2B sales force. Likely, their contracts will provide access to privileged marketing channels within the companies to drive employee adoption.

Compare that to the cost and complexity facing a traditional pharma sales force that needs to:

- Contract with payers (likely one by one at this early stage of market development)

- Entertain real world evidence (RWE) pilots

- Market to prescribers (likely starting with sleep centers as concentrated targets for chronic insomnia patients, but also needing to consider general psychiatrists and even primary care physicians to get to the entire market)

So, whereas the price tag for Somryst may be higher, the ultimate sunk cost of the selling model may also be higher, thus challenging the product’s profitability and its ability to capture the market. At the Somryst launch (notably during the COVID-19 pandemic), Pear partnered with a telehealth provider to provide direct links from the product’s website at a nominal $45 cost. The partner was likely trained on Somryst’s intended use but is not a guaranteed prescription.

How Will It All Net Out?

Because Somryst has succeeded in achieving an FDA label, it is uniquely positioned for a large market potential, both in terms of numbers of patients as well as revenue. Its closest competitor in terms of supporting clinical data, Sleepio, is only offered via employers, so the only direct competition is if a user is offered Sleepio at work but is aware they have an option to get Somryst via their healthcare provider. It is unclear how often this will happen. If it does happen, it is then unclear which option the patient will choose. But given Sleepio’s business model of being offered via employers at a significantly lower price, its market potential is smaller than Somryst’s overall.

And finally, because the VA’s product is free and messaged to a relatively restricted patient population, the market potential—in terms of both patient numbers and revenue—is quite low (zero in terms of revenue). But they can still impinge on Somryst’s and Sleepio’s market potential if users are aware of and decide to try the “free version” first. Time will tell if Sleepio and / or CBT-i Coach will make a play to expand their market potential by expanding their user base and / or adding to their overall data package, with a compensatory bump in price and marketing effort.

In the US, the prevalence of acute insomnia varies with one recent estimate at 9.5% with 1 in 5 becoming chronic, meaning that there are about 6.2 million chronic insomnia patients. This sizable market could go one of three ways:

- Towards PDTs favoring Somryst: The FDA could increase oversight of these products and ensnare Sleepio in its nets, causing a bit of a hiccup in their commercialization progress. Though, Sleepio’s existing evidence may allow it to quickly pivot into a 510(k) clearance using Somryst as the predicate! Also, payers could learn to love the FDA cleared product. Or, Pear’s product might prove to be far superior to Sleepio and importantly, demonstrate that in the real-world. Ultimately the PDT market potential here could be 6.2 million people at about $900 each, or around $5.6 billion.

- Towards DTx favoring Sleepio: In this scenario, regulation recedes—as was a threat with a now dead Federal Notice to deregulate some DTx apps—and/or the COVID EAU that allowed leniency for DTx to commercialize before regulatory review becomes permanent. This would allow unregulated DTx to take over the market. PDTs would be quickly outflanked. Ultimately the NDT market potential here could be 6.2 million people at about $100 each, or about $0.6 billion.

- Mixed market: In this scenario, FDA oversight and payer demands remain murky. Depending on individual target populations and/or products, markets develop very differently. Or potentially, the market could bifurcate the opportunity amongst the competitors, likely with less severe cases using Sleepio and more clinically “serious” cases using Somryst. The ultimate market will be somewhere in-between $0.6 – $5.6 billion but may be inefficient for sales models and frustrating for innovators due to uncertainty in buyers, access, and adoption.

Lessons for Biopharma

Despite Somryst’s high market potential, because the therapeutic basis itself is not theoretically differentiated from its competitors, it will remain vulnerable to the unregulated Sleepio and CBT-i Coach. Looking beyond chronic insomnia, how should a biopharma company mitigate the risks of entering other DTx markets via the “traditional” regulated PDT path?

Biopharma companies can consider four main levers to maximize their market opportunity and minimize competitive risk. The first two levers relate to the disorders / patient populations selected and the interventions used. The last two relate to the design of the DTx product itself:

- Target high-risk patients: Prioritize markets considered “high risk” where the impact of product failure is significant, e.g., suicide prevention, oncology, MDD or even TR-depression, etc. Non-prescription and / or free apps are less likely to attempt and successfully enter these spaces, leaving them for those that have FDA clearance. On the flip side though, these are more challenging populations so the development and probability of technical and regulatory success (PTRS) may be less attractive. But those are challenges that biopharma companies face daily. The industry’s whole model is to take on the risk as prudently as possible, navigate the regulation, and then get to market with a patented product. But keep in mind that as a medical device, the fast-follower could be more damaging as a 510(k) clearance is not difficult and there is no marketing protection on par with pharmaceutical approvals. So biopharma companies will need to do more to maintain the advantage.

- Leverage higher-risk / novel interventions: Part of the challenge with CBT-I market is that the standardized therapeutic approach can be easily replicated by fast followers. If the DTx or PDT incorporates more advanced interventions such as neurocognitive training, AR/VR environments, chatbots, etc. the need for regulation is likely more apparent and protective. Overall, CBT is everywhere in DTx right now so companies should be healthy skeptics about how they will compete and maintain an advantage with that well-known approach.

- Develop data-driven product features that differentiate: Feedback loops or flywheel approaches will leverage data-driven—likely user-driven—features that through network effects and user inputs become so much better than a follower can ever achieve. Think of Google running away with search because they cleverly maximized the user’s search behavior to continually improve search results. This could extend beyond DTx or PDTs to chatbots and other AI-driven approaches. Ultimately this type of feature would deliver a high barrier to competitors and protect the market. In CBT-I there is a potential with the sleep restriction / consolidation algorithm, but these are fairly ubiquitous and don’t seem complicated enough nor likely to reach that degree of differentiation.

- Build capabilities that maximize engagement: A key challenge for DTx (as with many therapeutics in general) is compliance and adherence. In order to deliver value at the individual level as well as build real-world evidence, a DTx product must create and maintain user engagement throughout the complete program. This can be a critical component of the differentiation mentioned above. Furthermore, each patient population that a DTx will target may very well have unique needs and desires that drive engagement. So, developing capabilities to “zero in” on these special sub-populations may prove a differentiator, especially for those companies with a portfolio of DTx offerings.

Final Considerations

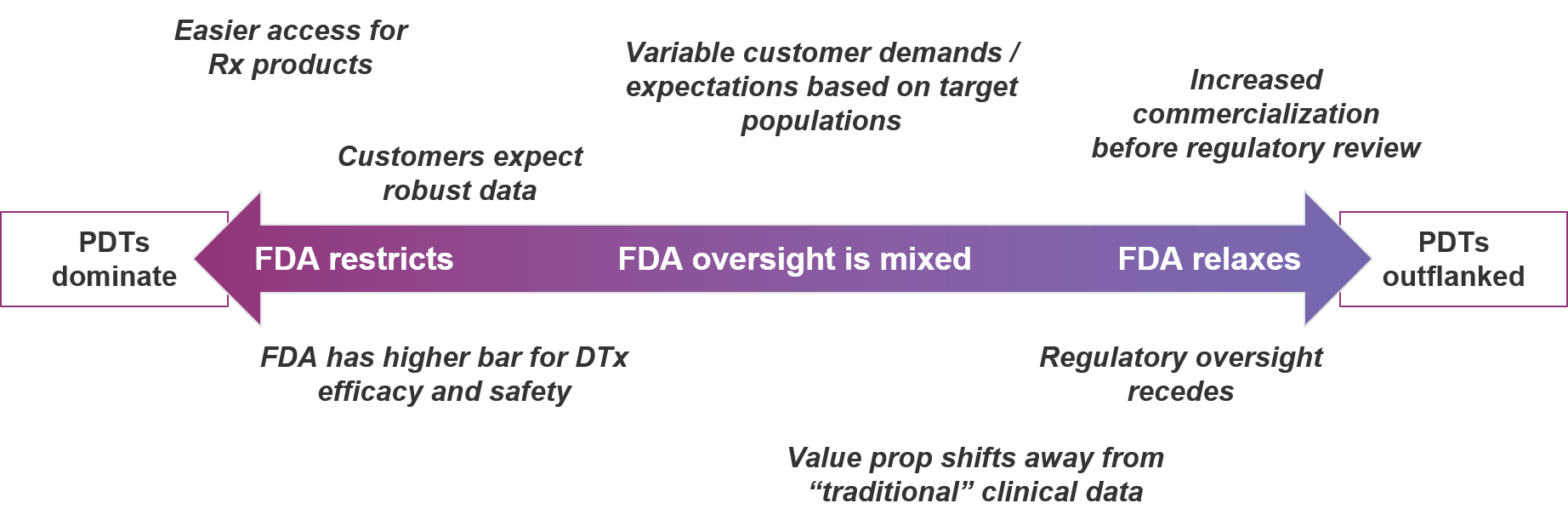

Of course, some aspects of the DTx market are external to the product development efforts of biopharma companies and competitors. Biopharma entrants should be aware of and consider contingency planning associated with various scenarios along the range of strict to relaxed regulatory oversight:

In conclusion, the DTx market is certainly an attractive space for biopharma companies to consider. However, new entrants must take care to mitigate competitive risk by carefully selecting which markets to enter. It’s looking awfully risky to be a prescription digital therapeutic in a market where non-prescription digital therapeutics can also play. Until the FDA—as well as insurers—provide a clearer picture of where each market exists, one must understand the risks, invest wisely, and have a plan for setting high barriers to entry in their wake.