Posted by Alex Zuniga, Jose Quejada, and Mahazabeen Sayyed on April 5th, 2022.

There’s no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic brought major disruption to people across the globe. Of course, it affected people’s health. But it also caused major shake-ups in people’s finances, as well as the ways in which they work, socialize, worship, and more – impacting all facets of personal and public life.

Interestingly, it also brought changes to the mental and behavioral health landscape, some negative and—in an indirect way—some positive. While the pandemic has significantly increased the incidence and prevalence of mental health problems, it has also caused regulators, providers and payers to focus more sharply on mental health issues. As a result, the resources available for mental health have increased. The question is, will that additional focus stay with us long-term…or will it fade into memory as the pandemic recedes?

In this article, we take stock of COVID’s impact on mental health and review how payers and other key stakeholders in the United States have adjusted. And while we don’t have a crystal ball, perhaps we can hazard a guess as to how enduring the new landscape will be.

COVID-19’s Overall Impact on Mental Health

According to the World Health Organization, there have been nearly 484 million cumulative COVID cases worldwide (as of late March, 2022).[1] For most, the focus has been on the physiological effects of COVID. However, scientists, healthcare professionals, and others have also noted COVID’s impact on CNS, particularly those associated with mental health.

Studies tracking patients who have had COVID are finding that they are more likely to develop mental health issues than those who did not contract the disease. A recent study published in The Lancet Psychiatry looked at 236,379 patients that had been diagnosed with COVID-19. 33.62% of those patients are estimated to have neurological or psychiatric issues within six months of diagnosis. These issues range from intracranial hemorrhage to anxiety disorders. In another study leveraging databases from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the overall risk of developing mental health issues within a year after contracting COVID-19 had a hazard ratio of 1.6, which translates into an additional 64.38 cases (over baseline) per 1,000 people.[2]

COVID-19’s mental health impact has not been limited to those who have contracted the disease. In fact, it’s had widespread effects on the psychological health of the general population.

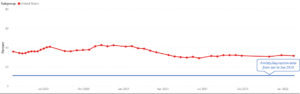

Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation illustrates how widespread COVID’s impacts have been. Their analysis of the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey showed that 31.5% of adults in the US reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder in January and February of 2022.[3] This was up from only 11% from January to June of 2019.[4] In fact, the reported rates of anxiety and depression have remained between 30% and 40% from April of 2020 on through the present (early 2022).[5]

These effects are attributed to a range of COVID-related stressors including job losses and financial insecurity, social isolation, and “burnout” from being a healthcare or other essential worker during the pandemic. Clearly, COVID’s effects have been widespread and have extended beyond the COVID patient population.

Table 1: Impact of COVID-Related Stressors

| Social Isolation |

|

| Financial Insecurity / Job Loss |

|

| Health Care / Essential Workers |

|

US Federal and State Government Reactions

To prepare for the influx of patients during the height of the pandemic, the US federal government declared a public health emergency (PHE). On the heels of this declaration, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the US Department of Heath and Human Services (HHS) took the necessary steps to provide additional resources for mental health and substance abuse disorders.

These actions resulted in increased access to resources and care for COVID-19 patients. However, they also served as a mechanism for improving behavioral and mental health services in general. For example, the PHE resulted in expanded coverage for telehealth services. CMS provided waivers for these services, private insurers added reimbursement plans for telehealth, and HHS also provided HIPAA flexibility.[13]

CMS expanded coverage for mental health services delivered via telehealth platforms, telephone, and similar mechanisms to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19. No-cost mental health counselling using 24/7 crisis support lines increased, as did webinars to provide stress and anxiety management education.[14] Programs initiated well-being checks via calls to enrollees such as older adults and isolated individuals.

In January of this year, the US HHS secretary Xavier Becerra extended the COVID-19 federal PHE declaration for an additional 90 days until at least April 16, 2022. This renewal marks the eighth time the federal government has extended PHE since it was first declared.[15]

Individual US states have also implemented their own public health emergencies which allows for out-of-state providers to offer telehealth services, as well as expands the reimbursement of virtual communication and e-consults. However, as of January 2022, over half of US states have ended their emergency declarations.[16]

US Payer Reactions

The PHE also served as a catalyst for payers to reshape their coverage and decision-making policies. Payers were able to redefine access to health services for COVID-related and non-COVID-related health conditions. Their actions included:[17]

- Increasing outreach to patients to provide them with educational information and updates during the pandemic.

- Reducing financial barriers to coverage for access to non-COVID-19 care, including waived requirements, late fees, and refill limits on 30-day maintenance medication prescriptions.

- Addressing COVID-19 related social health needs, including behavioral & mental health needs; Some payers began to develop initiatives to support health inequities in the U.S. including investing in support programs for mental and behavioral health (e.g., crisis text lines, domestic violence prevention programs, etc.), and began expanding access to telehealth services.

- Providing additional financial support for health care providers by eliminating utilization management protocols or prior authorization requirements for settings experiencing high in-patient, intensive care or post-acute care workloads.

- Supporting the distribution of medical supplies and services throughout the pandemic.

Payers have been able to invest heavily in behavioral and mental health services as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid shift towards telemedicine. To better illustrate the current payer landscape, we have summarized below how a few of the largest commercial payers have invested in non-COVID related healthcare issues, including behavioral and mental health services.

Table 2: Summary of Key Commercial Payer Investments Following the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

| Payer | Telehealth | Access to Non-COVID Healthcare | Investment / Partnership in Behavioral Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| UnitedHealth Group |

|

|

|

| Aetna CVS Health |

|

|

|

| Cigna |

|

|

Remaining Challenges Despite Increased Focus

Despite large payers’ interests in expanding behavioral / mental health offerings during the COVID pandemic, there have been challenges to suggest that payers may not be willing to sustain access to mental and behavioral health services.

Most notably, in August 2021, UnitedHealth Group paid $15.6 million in a settlement for wrongfully denied claims in mental health. An investigation by the US Department of Labor found that UnitedHealth would reduce reimbursement rates for out-of-network behavioral health services, would flag members who were undergoing mental health treatment for utilization reviews, and failed to sufficiently disclose information about its practices to plan sponsors and members, violating the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act.[37] Other large payers, such as Kaiser Permanente, have also faced similar lawsuits for not providing parity coverage for mental health.[38]

A report issued in January of 2022 by the US Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Treasury highlighted that many health plans may not be complying with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Act.[39] Under the recent legislation, health plans were required to perform and document comparative analyses of their non-quantitative treatment limits (NQTLs), the elements of a health plan coverage that are non-numerical (e.g., prior authorization, formulary design, etc.) to ensure they complied with parity law. 45 determination letters were issued related to NQTLs that were out of parity with medical and surgical benefits. This suggests a substantial portion of payers may not be adhering to parity mental health coverage, despite investing in it heavily over the course of the pandemic.[40]

Access to telehealth services has also been affected by the lifting of state-specific public health emergencies and policy changes. States have started to retighten their licensing rules, making it more difficult for physicians to provide telemedicine.[41] Additionally, payment parity for telehealth services (i.e., the same reimbursement rate as for in-person therapy) remains mixed across the US, with 27 states having no payment parity policies in place as of February 2022.

Opportunities & Considerations for Payers

Opportunities

Given the added focus on mental and behavioral health, payers have several opportunities that they can leverage. First, there is an opportunity for payers to embrace behavioral / mental health solutions as a key value proposition, establishing themselves as a major player in the behavioral health space. This could lead to more favorable patient and provider perceptions of these organizations, while also facilitating better access to care.

Payers also have an opportunity to proactively reassess their current offerings. In particular, they might consider investing more heavily in solutions that help prevent the onset of behavioral and mental health conditions in the first place.

From a governmental standpoint, access to telehealth services in mental health is a higher priority vs. other indications. This is evidenced by state-specific parity payment policies that are in place. Payers may be able to leverage this policy landscape to further invest in virtual solutions for mental and behavioral health.

Considerations

As we move forward, there are three considerations to keep in mind when trying to determine how durable the increased focus on mental health will be:

- The lifting of the federal PHE declaration in April of this year may remove the incentives that had previously allowed payers to increase access to mental and behavioral health services.

- Recent lawsuits of large commercial payers and increased scrutiny by the government may create a negative perception of payers’ coverage and decision-making processes.

- Payment parity for telehealth services is fragmented across the US and it remains to be seen how future policy will impact their reimbursement, introducing additional challenges for large, national payers.

Impact on Pharma Companies

Pharmaceutical companies investing in the mental and behavioral health space need to consider the impact of the changing payer landscape on access to their products. Understanding the challenges and opportunities that payers are facing will help shape payer engagement strategies and can positively impact the adoption of new solutions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has made a substantial impact on our society with ramifications expected to reverberate for a long time to come, especially within mental and behavioral health. To help mitigate the challenge, government authorities have incentivized payers to support mental health during the pandemic.

Payers have begun to invest heavily in mental health services, however challenges in reimbursement and access remain and the impact of future policy on telehealth and other services remains unknown.

As we emerge from the omicron surge and as public health emergencies are being lifted, the incentives and programs that have shaped the payer landscape are timing out. As a result, we are standing at a crossroads when it comes to access to mental and behavioral health services. Do we continue to invest in increased solutions and access to address the long-term psychological impacts of COVID and the lockdowns? Or will access revert back to pre-pandemic levels, potentially risking some people falling through the cracks?

The answer is uncertain, but the most likely outcome is somewhere between those two ends of the spectrum. It is likely that some pandemic-related policies and investments will roll back to pre-pandemic levels, while other solutions will be tough to pull back. As patients become accustomed to (for example) greater access to telehealth services—and as the body of data regarding their effectiveness grows—it’s likely that many new policies and solutions backed by evidence will stay in place, resulting in a positive outcome from a decidedly negative pandemic.

End Notes

[1] World Health Organization website, https://covid19.who.int/, accessed 03/30/22

[2] Berman, Robby, COVID-19 survivors: Increased risk of mental health issues, MedicalNewsToday, 02/23/22, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/covid-19-survivors-increased-risk-of-mental-health-issues#A-granular-analysis

[3] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Household Pulse Survey Data, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm, accessed 03/31/22.

[4] Kaiser Family Foundation website, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-reporting-symptoms-of-anxiety-or-depressive-disorder-during-covid-19-pandemic/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D, accessed 03/31/22.

[5] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Household Pulse Survey Data, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm, accessed 03/31/22.

[6] Pancani, et al, Forced Social Isolation and Mental Health: A Study on 1,006 Italians Under COVID-19 Lockdown, Frontiers in Psychology, May 21, 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663799/full

[7] Ibid.

[8] Evans, et al, Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample, Psychiatry Research, vol. 298, April, 2021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178121001165

[9] USA Facts, accessed 03/31/22, https://usafacts.org/state-of-the-union-2021/standard-living/

[10] Wilson, Jenna M. MS; Lee, Jerin MS; Fitzgerald, Holly N. MS; Oosterhoff, Benjamin PhD; Sevi, Bariş MS; Shook, Natalie J. PhD, Job Insecurity and Financial Concern During the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated With Worse Mental Health, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine: September 2020 – Volume 62 – Issue 9 – p 686-691,

[11] Ibid.

[12] Essential workers more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder during pandemic, American Psychological Association, March 11, 2021, https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/one-year-pandemic-stress-essential

[13] US Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/telehealth/index.html, accessed 03/31/22

[14] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, memo, June 29, 2020, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/Downloads/Mental-Health-Substance-Use-Disorder-Resources-COVID-19.pdf

[15] California Medical Association, news brief, January 14, 2022, https://www.cmadocs.org/newsroom/news/view/ArticleId/49631/US-extends-quot-public-health-emergency-quot-due-to-the-COVID-19-pandemic-1

[16] Alliance for Connected Care, web page, https://connectwithcare.org/state-telehealth-and-licensure-expansion-covid-19-chart/, accessed 03/31/22

[17] McLellan, et al, Health Care Payers COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs, NAM Perspectives, May 17, 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8406497/

[18] UnitedHealth Group website, https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/resource-library/news/Novel-Coronavirus-COVID-19/covid19-telehealth-services.html, accessed 03/31/22

[19] UnitedHealth Group website, https://www.uhc.com/member-resources/health-care-programs/mental-health-services, accessed 03/31/22

[20] American College of Physicians, summary document, https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/clinical_information/resources/covid19/payer_chart-_covid-19.pdf, accessed 03/31/22

[21] UnitedHealth Group news post, Partnership Aims to Expand Access to Behavioral Health Care in Washington State, https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/posts/2021/2021-07-28-partnership-expands-behavioral-health-care.html, July 28, 2021

[22] Aetna website, https://www.aetna.com/document-library/health-care-professionals/bh-televideo-service-codes-covid-19.pdf, accessed 03/31/22

[23] American College of Physicians, summary document

[24] Ibid.

[25] Aetna website, https://www.aetnainternational.com/en/about-us/explore/current-affairs/wysa-mental-well-being-app.html, accessed 03/31/22

[26] American College of Physicians, summary document

[27] Ryan, Tom, Will CVS make a breakthrough as it expands in-store mental health services?, RetailWire, May 4, 2021, https://retailwire.com/discussion/will-cvs-make-a-breakthrough-as-it-expands-in-store-mental-health-services/

[28] CVS website, https://www.cvshealth.com/news-and-insights/articles/aetna-launches-specialty-provider-network-to-prevent-suicide, accessed 03/31/22

[29] CVS website, https://www.cvshealth.com/news-and-insights/articles/aetna-and-equip-to-provide-virtual-treatment-for-eating-disorders, accessed 03/31/22

[30] Bryant, Bailey, Aetna, Inpathy Expand Virtual Behavioral Health Partnership, Nov. 3, 2020, Behavioral Health Business, https://bhbusiness.com/2020/11/03/aetna-inpathy-expand-virtual-behavioral-health-partnership/

[31] Cigna website, https://static.cigna.com/assets/chcp/resourceLibrary/medicalResourcesList/medicalDoingBusinessWithCigna/medicalDbwCVirtualCare.html, accessed 03/31/22

[32] Minemyer, Paige, Cigna grows digital behavioral health network in partnership with Talkspace, Fierce Healthcare, May 22, 2020, https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payer/cigna-grows-digital-behavioral-health-network-partnership-talkspace#:~:text=Cigna%20is%20expanding%20its%20digital,network%20for%20digital%20behavioral%20health.

[33] American College of Physicians, summary document

[34] Landi, Heather, Cigna plans to invest $450M in venture arm for digital health, analytics, Fierce Healthcare, Mar. 1, 2022, https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payers/cigna-plans-invest-450m-venture-arm-digital-health-analytics

[35] Cigna press release, Cigna Customers Can Now Work With Behavioral Health Coaches as Demand for Mental Health Support Surges, https://newsroom.cigna.com/behavioral-health-coaches

[36] Beerman, Laura, CIGNA’S EVERNORTH CONTINUES EXPANSION OF MENTAL HEALTH AND OTHER DIGITAL OFFERINGS, health leaders, Feb. 3, 2022, https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/payer/cignas-evernorth-continues-expansion-mental-health-and-other-digital-offerings

[37] Minemyer, Paige, UnitedHealthcare to pay $15.6M in mental health parity settlement, Fierce Healthcare, August 12, 2021, https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payer/unitedhealth-to-pay-15-6m-mental-health-parity-settlement

[38] Hutchings, Kristy, ‘We have never seen such an egregious case’: Inside Kaiser’s broken mental health care system, Fast Company, May 3, 2021, https://www.fastcompany.com/90631941/we-have-never-seen-such-an-egregious-case-inside-kaisers-broken-mental-health-care-system

[39] 2022 MHPAEA Report to Congress, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/laws-and-regulations/laws/mental-health-parity/report-to-congress-2022-realizing-parity-reducing-stigma-and-raising-awareness.pdf, accessed 03/31/22

[40] O’Connor, Katie, Government Steps Up Efforts to Enforce Parity Law, Psychiatric News, Mar. 1, 2022, https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.03.3.32

[41] Weiner, Stacy, What happens to telemedicine after COVID-19?, Oct. 21, 2021, https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/what-happens-telemedicine-after-covid-19, accessed 03/30/22